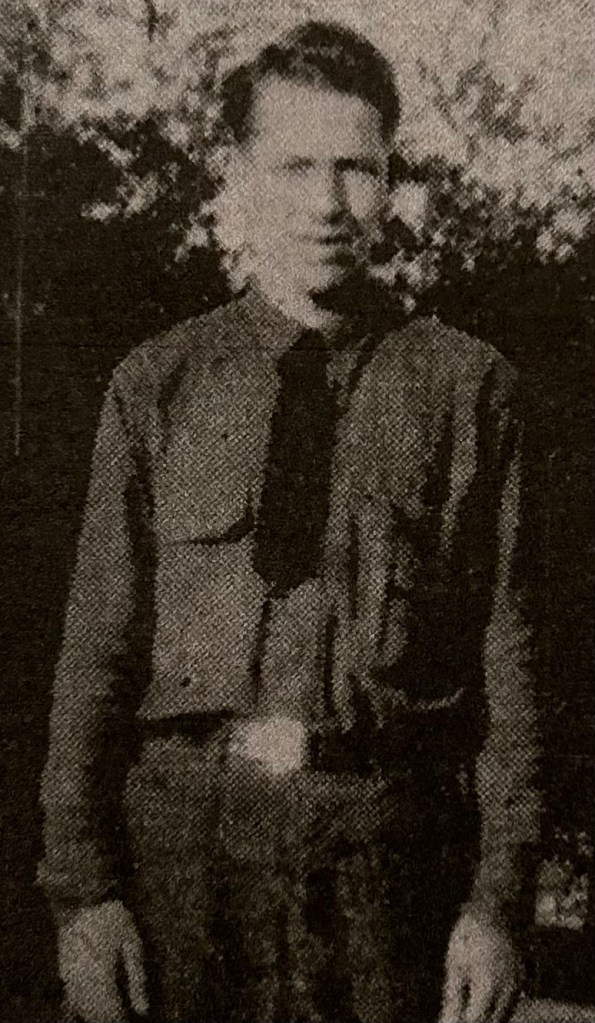

Private Earl Seibert came home yesterday, May 25, 2024. He’d been gone for a long time.

The mechanic from Allentown, Pennsylvania, died 82 years ago in a Japanese POW camp in the Philippines. He was buried there in a common grave.

His family knew he was missing and presumed dead. Not until World War II ended did they learn he had succumbed to diphtheria in 1942 at Cabanatuan Camp 1 on Luzon. He was 23. Early this year, the Defense Department announced his remains had been identified.

Seibert arrived at Philadelphia International Airport for a “dignified transfer” on May 21. Yesterday, the military and a throng of mourners paid tribute to him at Jordan United Church of Christ and Grandview Cemetery outside Allentown. I wrote about him in February, so I had a special interest in being there.

In the fall of 1941, Seibert and six hometown buddies shipped out to Luzon with the Army’s 803rd Engineer Aviation Battalion to work on airfields. They were at Clark Field when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and the Philippines. With the surrender in April 1942, they were among thousands of U.S. and Filipino troops taken on the Bataan Death March and held in squalid camps. Only three of the seven survived.

At the church service, Seibert’s niece Ginnie-Lee Henry shared a letter she wrote that begins “Dear Uncle Earl.” She told him that his father learned from the War Department in 1951 that his remains could not be recovered.

Both his parents and his sister – Henry’s mother – and then Henry herself “started to investigate what had happened to you.” It took many years. Henry found that when the prisoners couldn’t work or got sick, they were placed in housing the Americans called Barracks 0, so called because men had a zero chance of coming out alive.

“It is believed you were placed into Barracks 0 in the beginning of July 1942. Your personal belongings were taken by the Japanese guards, including your identification tag as a souvenir. The Army believes you died at 4 a.m. on July 27, 1942, having your death recorded on a condensed milk can label by another POW. You were one of twenty who died that day.”

Seibert’s cousin Tommy Sweeney, a private in the 20th Air Base Group, also was captured on Bataan. He died at the Cabanatuan camp June 23, 1942, of Vincent’s angina .

The POWs were exhumed at war’s end and reburied in the Manila American Cemetery, where the “unknowns” lay in a common grave. Six years ago, Henry and other family members provided their DNA to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. Last summer, it identified one set of remains as those of Seibert.

At the church yesterday, a half-open casket contained Seibert’s remains, enfolded in an Army uniform. His medals were on display, including a Bronze Star for his role in the defense of Bataan and two Purple Hearts, one because he was wounded January 16, 1942, and the other because he died at the hands of the enemy.

The Missing Man Table with a single chair was on display. On top of it was a folded American flag, a Bible, a candle, an inverted glass, a red rose in a vase tied with a yellow ribbon, a slice of lemon and some salt. The lemon is a reminder of a POW/MIA’s bitter fate. The salt symbolizes the family’s tears.

In times of sadness, there is comfort in ritual. I felt it.

Under the noontime sun, the casket rode to the cemetery two-and-a-half miles away in a horse-drawn carriage, to the clip-clop cadence of two Percherons’ hooves. A bugler played Taps. Riflemen fired three volleys in salute. We recited the 23rd Psalm aloud. With solemn respect, two soldiers lifted the American flag off the casket and folded it precisely. Another presented it to Henry as she sobbed. Three shell casings from the rifle salute were handed to her, symbolic of duty, honor, country.

“Welcome home, Uncle Earl,” Henry had written in her letter to him. “We remembered you. So did many others, too.”

wow. So happy his finally home

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLike

Hooyah!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really love these historic accounts. I feel like I know these soldiers after reading your vivid stories. Thank you for your great writings.

LikeLike

Thank you for writing. It seems you like these stories as much as I enjoy telling them. So glad I can put them out there for folks like you to read.

LikeLiked by 1 person