Over the last few weeks, I’ve been interviewing a 102-year-old World War II veteran about his experiences as a Navy weatherman in the Philippines.

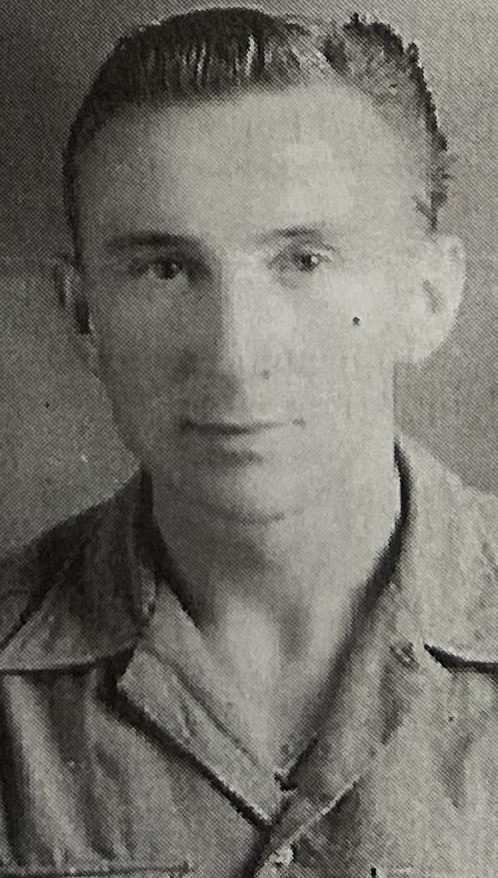

Robert Pearce grew up in Philadelphia and has lived in Lehigh County since the war. He is a former pilot and an organist who worked nearly five decades for Allen Organ Company. I had material that helped me put together his story — a memoir he wrote for his grandchildren a dozen years ago and a video of a talk he gave in 2023 for the Lehigh Valley Veterans History Project, which I attended.

My two-part “in their own words” war story is running in The Morning Call of Allentown. Part 1 appeared online March 19, and Part 2 the next day. It’s running in print this week.

I want to share with you an anecdote Pearce told me that isn’t in the story. It’s gruesome but reflects the reality of life on Palawan, which until early 1945 was occupied by the Japanese. The island is etched in World War II history as the place where, on December 14, 1944, Japanese troops executed 139 American POWs. It happened near the town of Puerto Princesa, where the enemy had an airfield.

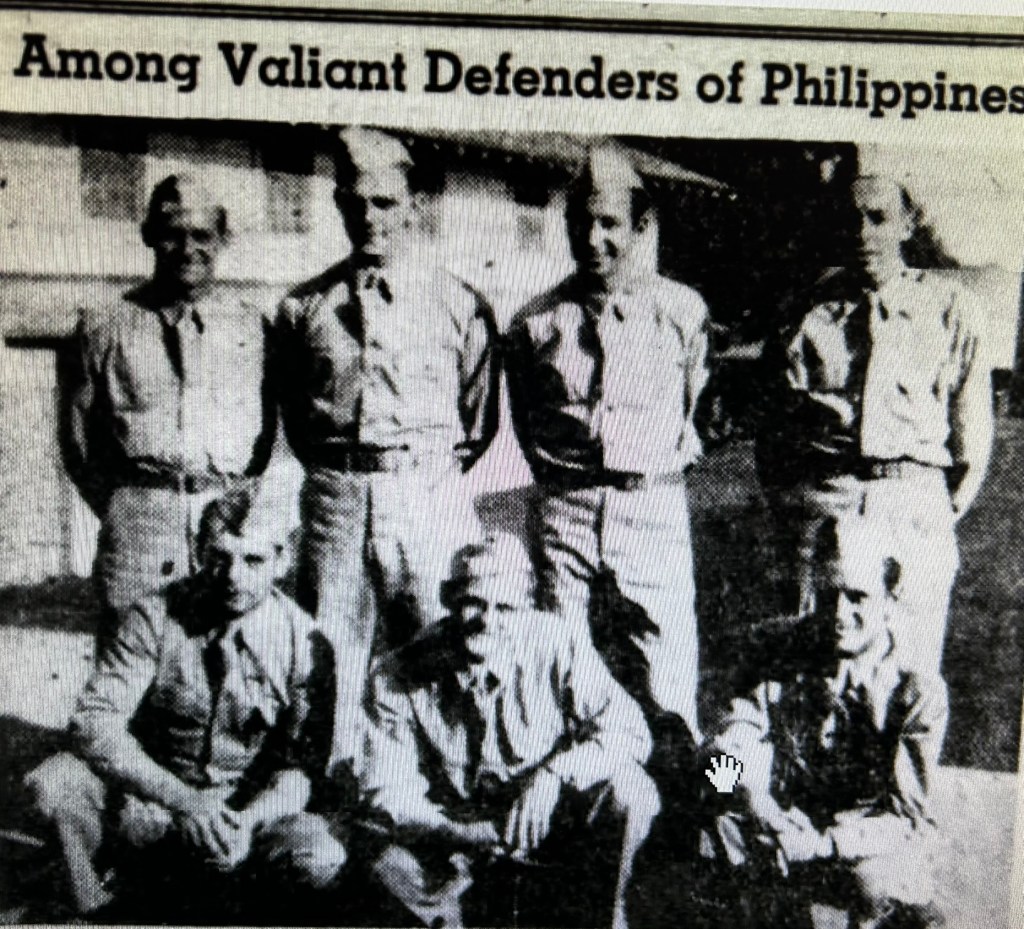

U.S. planes bombed the town for four months. Then at the end of February 1945, part of the Army’s 41st Infantry Division landed there and captured the airfield. The Puerto Princesa strip was rebuilt and used by the 13th Air Force Fighter Command until war’s end.

Pearce’s Navy unit, Fleet Air Wing 10, arrived in mid-April. It was tasked with conducting patrol plane operations against shipping in the South China Sea and along the Indochina coast. An aerographer’s mate first class, Pearce ran a weather office of six enlisted men. Their officer was Art Lund, a leading singer with the Benny Goodman Orchestra. Pearce and Lund would fly out to ships at sea, where Lund would entertain the men as Pearce accompanied him on the organ.

Pearce remembered episodes of horror at Puerto Princesa — fatal plane crashes on the airfield and, far more disturbing, Filipino revenge on the Japanese.

“The natives were primitive,” Pearce said. “They loved us because we were helping to ferret out the hated Japanese soldiers who were hiding out on the north side. Their thing was to capture one, chop his head off and proudly carry it by the hair through our camp. This time it was in front of the chapel while I was talking to the chaplain and some others. The chaplain shouted, “I want every man down on his knees!” He did not address the Filipino, and let him pass.

“Hatred of the Japanese was fueled by the fact that when they had the island, rape and killing were common.”

—

A search of Pearce’s name on Newspapers.com turned up a gem.

Pearce was a 19-year-old Navy trainee at Bainbridge, Maryland, at the end of 1942. He wrote a song that was performed by the boot camp’s stage band. He wasn’t married but wrote the lyrics as if he were a husband and father.

I’d love to be at home for Christmas,

But it’s my duty to be here.

When the snow is drifting on your window,

I’ll be thinking of you, dear.

I’d love to see our kids at Christmas,

Watch them tripping down the stair,

See them picking up each toy I sent them,

I can just picture them there.

I don’t like to talk about the war.

It seems that’s all one ever hears.

We all know what we’re fighting for:

A home that’s safe through the years.

I’d love to be at home for Christmas

At the end of ’43.

But my darling you must not expect us

Till we march home in victory.

In the first days of 1943, the Associated Press reported on a flurry of songs being written by sailors at Bainbridge Naval Training Center. It ran in newspapers across the country. “Embryo tars write songs at Bainbridge” was the headline in the Anderson Herald of Indiana. The subhead was: “Musicians are affected by the newness of mushroom camp on Susquehanna.”

Of Pearce, AP writer James E. Hague wrote:

“The Bainbridge charm worked even more quickly on Robert Pearce, ex-organist from Philadelphia. A week after his arrival, he wrote words and music — while on cleaning detail — for the top song of the Bainbridge ‘Hit Parade’ — ‘I’d Love to Be Home for Christmas.’

“If sailors could whistle while they work, its easy-to-whistle melody would be chirped by half the sailors at the station. And its popularity shows no signs of flagging.”

Pearce didn’t know about the story until I showed him the clip. He was delighted.