It is a Page 1 roll call of 1944 casualties.

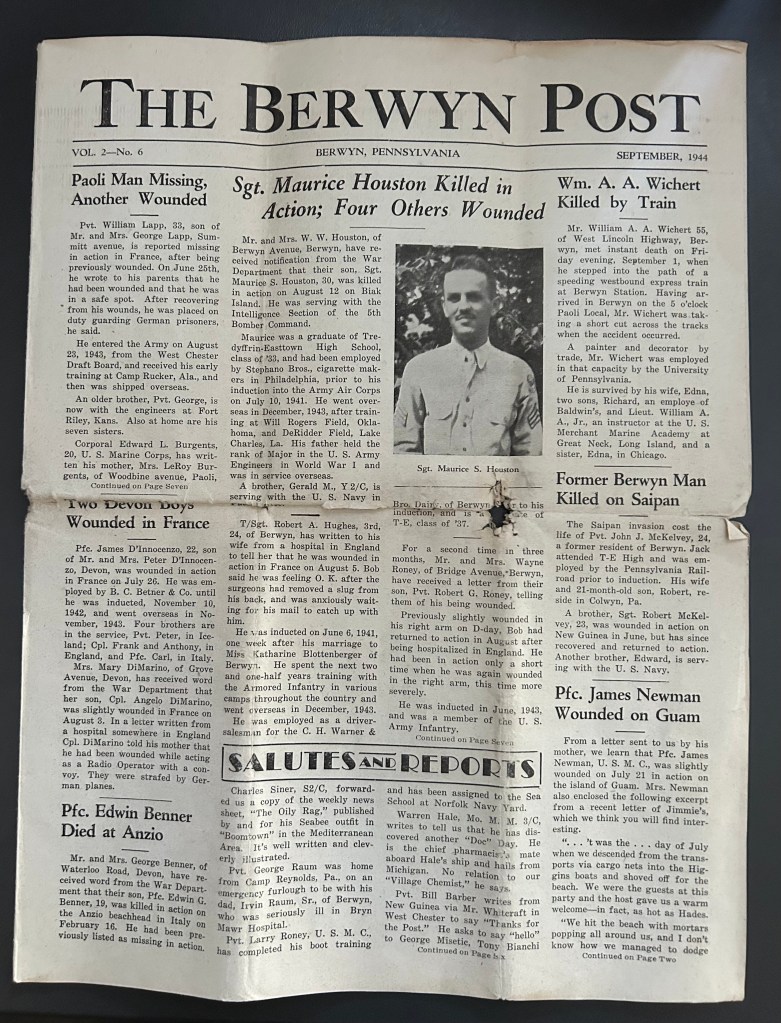

Army Air Corps Sergeant Maurice Houston, 30, son of a First World War officer, was killed in action August 12 in Indonesia. Private John McKelvey, 24, married with a toddler son, was killed on Saipan. Private First Class Edwin Benner, 19, was killed February 16 on the Anzio beachhead.

Marine Private First Class James Newman was wounded July 21 on Guam. Army Private First Class James D’Innocenzo, 22, was wounded July 26 in France. Army Corporal Angelo DiMarino of Devon, whose family and mine had a connection broken by a terrible accident, was slightly wounded in France on August 3 while in a convoy strafed by German planes.

Those casualties appear in the September 1944 issue of The Berwyn Post, a monthly tabloid published on Philadelphia’s Main Line “by Berwyn men and women on the Home Front for the Berwyn men and women on the Fighting Fronts.” The masthead notes the paper went to all graduates and students of Tredyffrin-Easttown High School in the service, by arrangement with the Paoli-Berwyn-Malvern Rotary Club. If you were in the military and a Berwyn resident or T-E grad, your subscription was free. Others in the service and civilians got the paper for a small price.

My dad graduated from Tredyffrin-Easttown in 1944 and went on to join the Coast Guard. But I’m not sure that’s how I happen to have this slightly torn eight-page issue of The Post. Still, when I found it in my file cabinet a few weeks ago, I couldn’t put it down. You can see how popular it must have been. Main Line servicemen and women all over the world were getting news from home about people they knew. They saw photos of hometown buildings and street scenes. They could read about the high school’s sports teams. They could turn to The Chaplain’s Corner for inspiration from the likes of Methodist minister Henry F. Hamer Jr., who wrote that “faith is the most precious of our possessions” and gave advice on how to keep it. On the front page, they learned what was most compelling: Who among them would not return?

The inside pages are full of chatty columns. A Mailbag takes up more than two full pages. In one typical letter, Army Corporal Norman L. Duncan writes from France: “Seems kind of tough to be in a country where most of the people are trying to be friendly and you can’t ever hold a conversation with them due to not being able to speak or understand their language. However, we are kept too busy to have any time to mingle with them. Let me tell you this sleeping in a ‘foxhole’ isn’t at all what it’s cracked up to be, especially if it is pouring rain. Food was rough for a while but is getting better every day and I don’t imagine it is going to be too tough.”

The paper printed excerpts from a letter James Newman, the Marine wounded on Guam, wrote to his mom: “[W]e descended from the transports via cargo nets into the Higgins boats and shoved off for the beach. We were the guests at this party and the host gave us a warm welcome — in fact, as hot as Hades.

“We hit the beach with mortars popping all around us, and I don’t know how we managed to dodge them and start our individual jobs. I was up with the infantry for about a week and I saw plenty of the sights that I’ve heard so much about since this war started. The infantry — honest to goodness — is the best there is, they are real artists when it comes to exterminating Japs. I saw them knock out three Nip tanks in one day and it is amazing how they all work together, calm, collected and with precision adjustment.”

Navy flyer Larry B. Mercer of Berwyn got a Commendation Ribbon for “meritorious and efficient performance of duty as air gunner of a dive bomber in an attack on enemy shipping in Rabaul Harbor, New Britain Island, on Nov. 11, 1943.”

The Post ran a picture of him and the complete text of his citation. Part of it states “Mercer, by maintaining a heavy and accurate fire from his gun against large numbers of enemy fighter planes, assisted materially in repelling their assault against the bomber formations.” The four-paragraph story adds Mercer was awarded a Purple Heart for wounds suffered at Tarawa and that he was now in California awaiting his next assignment.

The Post masthead lists its editors as the Rev. Elbert Ross, William W. Eadie, Charles T. Smith, Theodore Lamborn Jr. and Joseph Kelly. In bringing the war home, and home to those in the war, they served their community well.

Angelo DiMarino, the wounded Army corporal I mentioned above, was an older brother of John DiMarino, who was engaged to my aunt Josephine Venditta of Malvern. John was killed in a B-24 training accident on April 5, 1944. I wrote about him in my December 2, 2021, blog “How a WWII bomber crash in Colorado hit home.”