Thirty years ago, while trying to find out how my cousin Nicky died in Vietnam, I struck up a friendship with a retired Army colonel who figured in the story. He also had been caught up in a deeply controversial episode of the war and had much to say about how the military handled bad publicity. It’s an issue that resonates today.

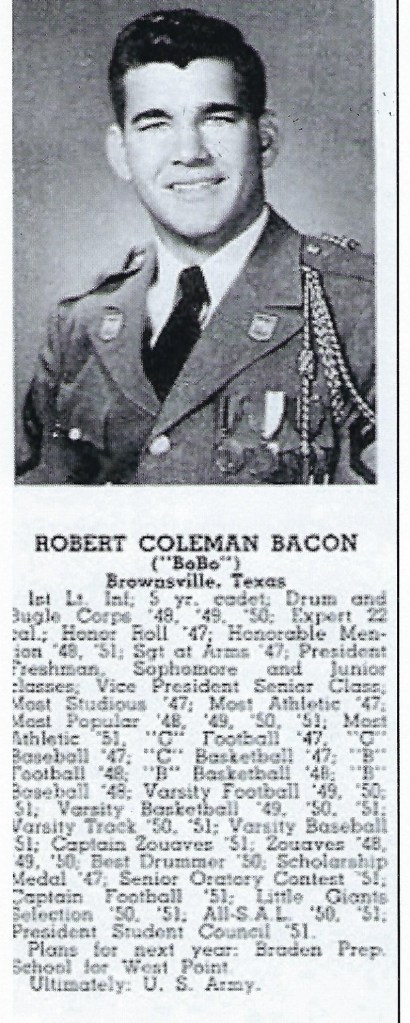

Robert C. Bacon of Columbia, South Carolina, was a West Point graduate who served two tours in Vietnam, the first in 1963-64 as an adviser to a South Vietnamese battalion, a role that put him on the cover of Life magazine. In the second, from 1969-70, he briefly headed a unit that provided training and orientation for troops newly arrived at Chu Lai, the Americal Division base along the South China Sea.

Nicky, a 20-year-old Army helicopter pilot, was among the soldiers who landed there in July 1969. On his sixth day in Vietnam, he was trucked to a firebase called LZ Bayonet for a class on grenade safety. The sergeant/instructor, in a gimmick to get the men’s attention, unwittingly tossed a live grenade onto the floor. Nicky lost a leg from the blast and died five days later, on July 15, at Chu Lai’s 312th Evacuation Hospital. Back home in Malvern, Pennsylvania, his parents received a bereavement letter from Bacon, commandant of the 23rd Adjutant General Replacement Company, the Americal Combat Center.

Except that they didn’t, really.

(Kadet Yearbook)

I’d hoped Bacon could help me understand what happened in the classroom but was in for a disappointment. When I first spoke with him in 1996, he said didn’t join the replacement company until five days after Nicky died. He refused to sign the letter that was dropped on his desk, because the “horrible, unfortunate accident” didn’t happen “on my watch” and he had no first-hand knowledge of it. Someone signed the letter for him.

If he had been in charge earlier, Bacon said, he would have halted the grenade-tossing routine as too dangerous.

“It is still hard to believe the attention-getting stunt the sergeant used,” he wrote to me. “One of the best attention-getters was to say at the start of the class, ‘Probably either you or the man sitting next to you will be killed or wounded during your tour. If you pay attention, it might not be you.'”

Lieutenant Colonel Bacon went on to lead the 3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry of the 196th Light Infantry Brigade and earned a Silver Star for gallantry. His name appeared in news accounts around the world after troops under his command reportedly mutinied in the Song Chang Valley near Da Nang. He reassigned the inexperienced lieutenant whose men were involved, saying at the time that he “wasn’t satisfied with the progress the company was making.” Pointedly, he always maintained there had been no mutiny.

My story on Nicky’s fate, two decades in the making, would become a book. I stayed in touch with Bacon almost until his death eight years ago, giving him updates on my research and further questioning him as more information came to light. He encouraged me in phone calls and in cards and letters he signed “Bobby,” and invited me to visit him, which I was never able to do. He eagerly shared letters, articles and other remembrances of his Army experience, in particular those concerning the so-called mutiny of Alpha Company in August 1969.

***

The Pentagon’s evasive posture over the blasting of alleged drug-runners’ boats in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific sent me thumbing through my thick folder on Bacon. One of the items he’d sent me was a term paper he wrote for the Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1973 while pursuing a master’s degree. The paper was for a communications class. In it, he cites the “mutiny” episode as a case study in botched public relations.

His advice to the Army hierarchy on what to do when bad news breaks? Come clean, and do it promptly.

Before you read Bacon’s paper below, I’ll show you the 1969 news story in The New York Times that rankled him for the rest of his days. It ran at the top of Page 1 on a Tuesday and was written by Associated Press staffers Horst Faas and Peter Arnett, both of whom had won Pulitzer Prizes for their coverage of the war — Faas in 1965 for combat photography, and Arnett in 1966 for international reporting. Bacon protested that the story was unfair; they responded respectfully that it was “absolutely fair.” Here is the complete article, followed by the writers’ letter to Bacon addressing his complaint:

Told to Move Again

On 6th Deathly Day,

Company A Refuses

The following dispatch is by Horst Faas and Peter Arnett of The Associated Press.

SONGCHANG VALLEY, South Vietnam, Aug. 25 — “I am sorry, sir, but my men refused to go — we cannot move out,” Lieut. Eugene Shurtz Jr. reported to his battalion commander over a crackling field telephone.

Company A of the 196th Light Infantry Brigade’s battle-worn Third Battalion had been ordered at dawn yesterday, to move once more down the jungled rocky slope of Nuilon Mountain into a labyrinth of North Vietnamese bunkers and trench lines 31 miles south of Da Nang.

For five days the company had obeyed orders to make this push. Each time it had been thrown back by invisible enemy forces, which waited through bombs and artillery shells for the Americans to come close, then picked them off.

Colonel Lost in Crash

The battalion commander, Lieut. Col. Robert C. Bacon, had been waiting impatiently for Company A to move out. Colonel Bacon had taken over the battalion after Lieut. Col. Eli P. Howard was killed in a helicopter crash with seven others. Since the crash Tuesday the battalion had been trying to get to the wreckage.

Yesterday morning Colonel Bacon was leading three of his companies in the assault. He paled as Lieutenant Shurtz told him that the soldiers of Company A would not follow orders.

“Repeat that, please,” the colonel said without raising his voice. “Have you told them what it means to disobey orders under fire?”

“I think they understand,” the lieutenant replied, “but some of them simply had enough — they are broken. There are boys here who have only 90 days left in Vietnam. They want to go home in one piece. The situation is psychic here.”

“Are you talking about enlisted men, or are the N.C.O.’s also involved?” the colonel asked.

“That’s the difficulty here,” Lieutenant Shurtz said. “We’ve got a leadership problem. Most of our squad and platoon leaders have been killed or wounded.”

At one point in the fight, Company A was down to 60 men, half of its assigned combat strength.

Bunkers Believed Empty

The colonel told Lieutenant Shurtz: “Go talk to them again and tell them that to the best of our knowledge the bunkers are now empty — the enemy has withdrawn. The mission of A company today is to recover their dead. They have no reason to be afraid. Please take a hand count of how many really do not want to go.”

The lieutenant came back a few minutes later: “They won’t go, colonel, and I did not ask for the hand count because I am afraid that they all stick together even though some might prefer to go.”

The colonel told him: “Leave these men on the hill and take your C.P. element and move to the objective.”

The lieutenant said he was preparing to move his command post and asked: “What do we do with the ammunition supplies? Shall we destroy them?”

“Leave it with them,” the colonel ordered.

Little Comforts Missing

Then Colonel Bacon told his executive officer, Maj. Richard Waite, and one of his Vietnam veterans, Sgt. Okey Blankenship, to fly from the battalion base across the valley to talk with Company A.

“Give them a pep talk and a kick in the butt,” he said.

They found the men exhausted in the tall, blackened elephant grass, their uniforms ripped and caked with dirt.

“One of them was crying,” Sergeant Blankenship said.

The soldiers told why they would not move. “It poured out of them,” the sergeant said.

They said they were sick of the endless battling in torrid heat, the constant danger of sudden firefights by day and the mortar fire and enemy probing at night. They said that they had not had enough sleep and that they were being pushed too hard. They had not had any mail or hot food. They had not had any of the little comforts that made the war endurable.

Helicopters brought in the basic needs — ammunition, food and water — at a tremendous risk under heavy enemy ground fire. But the men believed that they were in danger of annihilation and would go no farther.

Major Waite and Sergeant Blankenship listened to the soldiers, most of them a generation younger, draftees 19 and 20 years old.

Sergeant Blankenship, a quick-tempered man, began arguing.

“One of them yelled to me that his company had suffered too much and that it should not have to go on,” Sergeant Blankenship said. “I answered him that another company was down to 15 men still on the move — and I lied to him — and he asked me, ‘Why did they do it?’ “

“Maybe they have got something a little more than what you have got,” the sergeant replied.

“Don’t call us cowards, we are not cowards,” the soldier howled, running toward Sergeant Blankenship, fists up.

Sergeant Blankenship turned and walked down the ridge line to the company commander.

The sergeant looked back and saw that the men of Company A were stirring. They picked up their rifles, fell into a loose formation and followed him down the cratered slope.

***

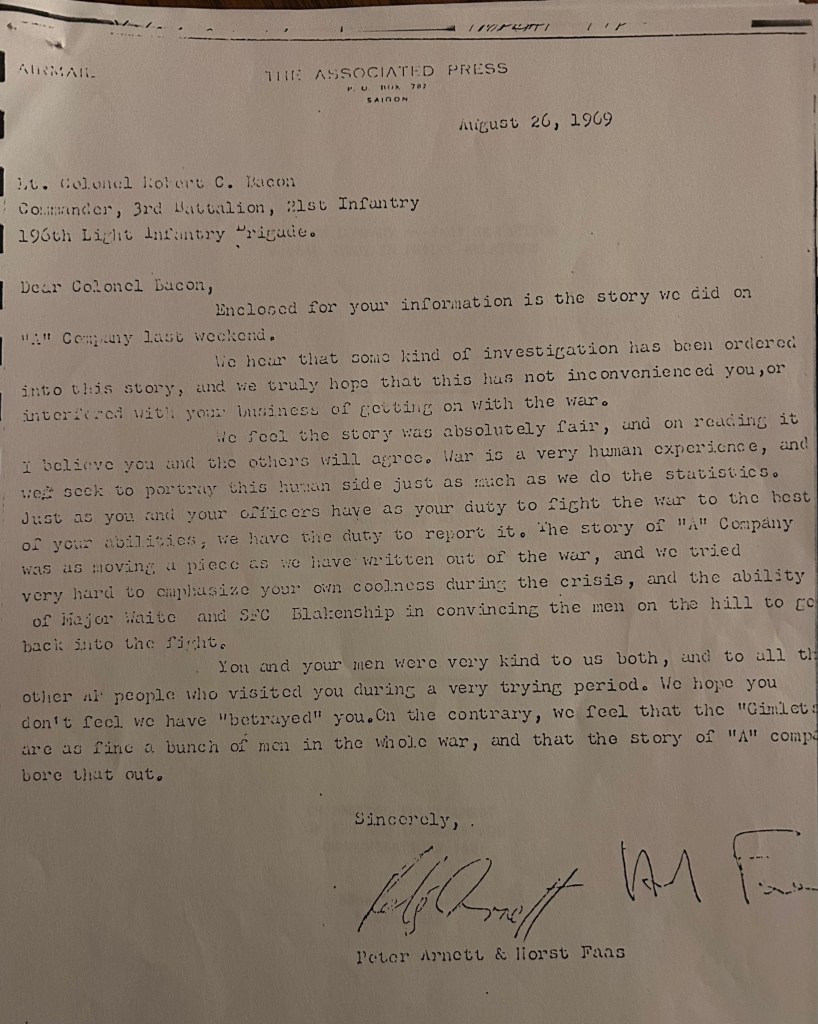

Bacon complained about the story to Arnett and Faas. He sent me a copy of their response. Here it is:

The Associated Press

P.O. Box 702

Saigon

August 26, 1969

Lt. Colonel Robert C. Bacon

Commander, 3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry

196th Light Infantry Brigade

Dear Colonel Bacon,

Enclosed for your information is the story we did on “A” Company last weekend.

We hear that some kind of investigation has been ordered into this story, and we truly hope that this has not inconvenienced you, or interfered with your business of getting on with the war.

We feel the story was absolutely fair, and on reading it, I believe you and the others will agree. War is a very human experience, and we seek to portray this human side just as much as we do the statistics. Just as you and your officers have as your duty to fight the war to the best of your abilities, we have the duty to report it. The story of “A” Company was as moving a piece as we have written out of the war, and we tried very hard to emphasize your own coolness during the crisis, and the ability of Major Waite and SFC Blankenship in convincing the men on the hill to go back into the fight.

You and your men were very kind to us both, and to all the other AP people who visited you during a very trying period. We hope you don’t feel we have “betrayed” you. On the contrary, we feel that the “Gimlets” are as fine a bunch of men in the whole war, and that the story of “A” company bore that out.

Sincerely,

Peter Arnett & Horst Faas

***

Here is Bacon’s Army War College paper:

MUTINY IN COMPANY A — FACT OR FICTION

A CASE STUDY IN PUBLIC RELATIONS

By Robert C. Bacon

March 1973

For most Americans, 26 August 1969 started as a typical hot summer Tuesday … that is until they had their first cup of coffee and opened their morning newspaper. It was at that moment that many were startled and stunned by headlines such as “Company A Refuses to Go,” or “Weary Viet GIs Defy Orders.” Their shock was warranted, for this appeared to be the first large-scale combat refusal by U.S. soldiers in over seven years of participation in the war. The message was not confined to the United States, as was pointed out by David Lawrence in his article in U.S. News & World Report titled “What’s Become of Voluntary Censorship?”

“… [T]he dispatch which revealed that American troops were engaged in a mutiny was promptly spread around the world. The North Vietnamese officials read it, and so did the leaders in Moscow and Peking. The impression was conveyed that the United States had on its hands an incipient rebellion in the ranks of its armed services. Broadcasts by Viet Cong radio hailed the news and predicted more such incidents would follow.”

Others felt that the alleged incident was having a profound impact on President Nixon. For example, in The New York Times of 27 August, James Reston in a commentary entitled “A Whiff of Mutiny” inferred that the president now had to consider a revolt by all the military men in Vietnam. Similar inferences were undoubtedly drawn by enemy negotiators at Paris who were undoubtedly encouraged to postpone any concessions toward a peaceful resolution of the war.

Since the incident took place several years ago, the entire initial article by Horst Faas and Peter Arnett is repeated on the following page as it appeared in The New York Times of 26 August 1969.

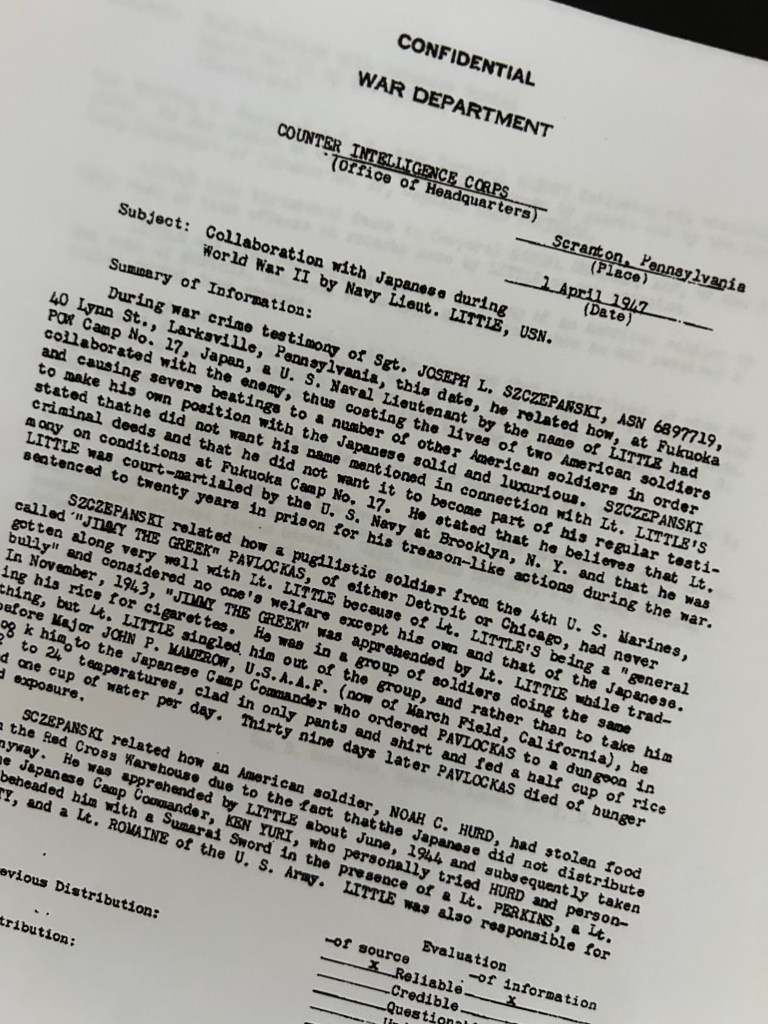

In the next few days following the release of the article, nothing was done on the part of the Army to refute or explain had had actually happened. The complete vacuum of press releases by the Army undoubtedly occurred because:

— The article came as a complete surprise and had not been anticipated even by those members of the Army directly involved in the incident.

— The Army, for a period of three days, closed the gates of communication to other members of the press corps who were trying to dig deeper into the story.

Thus, two cardinal rules of good public relations were violated:

— Anticipate adverse publicity as it is developing and be prepared to react.

— After an incident occurs, maximum disclosure with minimum delay should be the standard.

Why wasn’t the story anticipated? Principally it was because I, as the battalion commander, did not view it in the same light as the two reporters. To me, the entire unit, including Company A, had fought a magnificent and courageous battle over a period of six days against very tough opposition. Company A had hesitated to get into battle for a period of about 55 minutes only because their inexperienced and battle-weary company commander had failed to give them a direct order to do so. Accordingly two days before the article had appeared in the news, I had relieved the company commander and praised the soldiers in Company A. At the time, I would have thought it was incredible that anyone could have inferred that the entire company had been cowardly and refused to fight.

Further, it was anticipated that any stories by Mr. Faas and Mr. Arnett would be centered around the combat actions of the battalion as well as the recovery of their compatriot, Mr. Oliver Noonan, [a freelance photographer for The Boston Globe] who had been shot down in a helicopter in the early phase of the battle. Further, neither Mr. Arnett nor Mr. Faas had ever been with Company A or any of its members during any part of the operation. They were quite congenial when they departed — asked no questions about Company A and appeared only interested in verifying their account of the operation. This initial assessment of what they might write appeared to be substantiated by articles in the Times on 24 and 25 August. In these articles, the battle and the recovery of Mr. Noonan were well-covered in detail, and it was not until 26 August [that] the balloon burst.

In reflection, perhaps the single most important reason I did not anticipate or expect an article of this nature was my previous experiences long ago with Mr. Faas and other members of the press corps. Perhaps I might have been more wary had the information officer or someone else clued me in on the subtle change and pressures on the press corps since my previous assignment in Vietnam.

On my first tour in 1963-64, there were few Americans in the field, and it was not uncommon to have a member of the media tag along on an operation. The first correspondent I recall encountering was Mr. Larry Burrows, who was killed about two years ago [in 1971] when his Vietnamese helicopter was shot down over Laos. Larry was courageous, professional, attended his own needs in the field and was a pleasure to be around. In June of 1964, he took a picture of me that ended up on the cover of Life magazine, and in the same issue was some very objective reporting on atrocities by both the Viet Cong and South Vietnamese soldiers. Horst Faas was a lot like Larry and got his job done with a minimum interference with the operation. His photographic skills and moving dialogue graced many newspapers in those days. Particularly impressive was a story he did on the Viet Cong bombing of a floating Chinese restaurant in Saigon. Once, I asked why he didn’t use any Japanese cameras and fondly recall his reply in a thick German accent — “One thing about a Leica, it always works.”

In those days, the press corps in Saigon was primarily composed of tested, experienced, responsible, mature combat correspondents. While I might not have liked what they had to say in some articles, it was normally always objectively reported and well-documented. Later, with the surge of U.S. units, younger, less experienced correspondents flooded into Saigon. These [Y]oung Turks knew where the action was, and some would go to any extreme to sensationalize to get that all important byline on the front page of major newspapers. Some of the most stirring accounts of battles were written by some of these men who never got out of Saigon. Their reports were strictly based on what they had picked up at the daily press conference, spiced up with information they had picked up at the local bars. These grandstand plays by the [Y]oung Turks undoubtedly put extreme pressure on some of the older correspondents to sensationalize. Unfortunately, I was unaware of this metamorphosis in the press corps. Hence, without benefit of a pre-brief by the information officer, I considered Horst Faas to be as responsible, objective and mature as in our early encounters. I should have suspected he had changed when, after being out in the field for about six hours, I had to give him half a canteen of water.

Well, this leads to perhaps the most important rule in public relations:

— Know your reporter/advisory [sic].

Some will be experienced, sympathetic, objective and responsible. Others will quote you out of context, distort the facts or maybe even sensationalize. Forewarned is fore-armed. Always get your public affairs/information officer to give a pre-brief so that you will be prepared for the challenge.

In this particular incident, I was taken completely by surprise. Mr. Faas and Mr. Arnett must have known they were sitting on a gold mine and felt the same sense of euphoria as an addict that mainlines for the first time.

When the story broke, we couldn’t believe it and were in a momentary state of shock. We quickly recovered and wanted to set the record straight, and even without any public relations background, realized that time was critical and any impact to contradict or explain the situation had to be done quickly. The communication to explain what had transpired was in our hands.

— The company did not fail to obey an order. They were never given an order. When an order was given, the entire unit had moved out.

— The article was written as a first-hand account, yet neither Mr. Faas or Mr. Arnett was ever with the unit and had not talked with a single soldier in Company A.

— The hesitation lasted about 55 minutes, and the company was still in the field doing a good job.

Other points could be mentioned, but the big problem, for some unexplainable reason, was a blockout [sic] imposed on the media for two days. Why the Army didn’t follow a policy of maximum exposure with minimum delay still astounds me.

The location of my unit was, as they say in Army jargon, out in the boonies. The only way we could be reached was by helicopter. When the reporters finally arrived, we told the story as honestly as possible and invited them out to see Company A, which was still in the field.

The following are some quotes from articles that appeared some time after the incident, which if released in a timely manner might have overcome some of the adverse publicity of the original article.

In Newsweek, 8 September, in a commentary titled “The Alpha Incident”: “… [T]he article a gross injustice to all concerned.”

In Pittsburgh Press, 2 September 1969, in an interview with Specialist 4 Curtis, a member of Company A: “We never at any time said we wouldn’t go down the hill. … When Lieutenant Shurtz gave us a direct order, we started moving.”

In Time, 8 September 1969, in an article “Incident in Song Chang Valley”: “Neither Faas or Arnett saw or spoke to anyone in Alpha first hand. … [T]heir report that nearly all the soldiers of A Company broke was plainly exaggerated.”

In Detroit News, 2 September 1969: “Captain Bligh would have sniffed with a Charles Laughton disdain had anyone suggested to him the incident … was mutiny, which is how some commentators have described it.”

In Waterville, Maine Morning Sentinel, 13 September 1969, interview with [Private First Class] Batchelder, A Company, who lived in Dexter, Maine: “Please let the people know that this company is not chicken. We lost half our company and were exhausted from five days of fighting. … There was no mutiny, and to say otherwise is a disgrace.”

While there is no way of knowing the impact of these articles, we could certainly conclude that it was somewhat less than if they had been dispatched in a timely manner. At least this would have caused the public to look at other facets of the issue. Perhaps then they might have come to the conclusion that no one relishes the thought of going into battle. That the soldiers in Company A were tired and frightened and hesitated on going into battle primarily because their company commander could not meet the awesome challenge of ordering them to do so. Finally, they might have concluded, as I did, that Company A was a very courageous company that overcame their infectious fear and accomplished their mission in a truly outstanding manner.

It is not the purpose of this paper to be overly critical of Mr. Faas or Mr. Arnett. They both were undoubtedly under pressure to get a big story whenever they could. Had they bothered to check more deeply prior to publishing the story, they too might have come up with a different version. Their story was based on what they overheard on the radio and a conversation with a sergeant [Blankenship] who I had sent out to Company A. Considering their sources, the article could be classified as object [sic], albeit not in-depth, reporting. Certainly the letter they dispatched to me, on the following page, would indicate their sincerity.

To me, there is a contradiction between the actual article and the last sentence in the letter. I cannot see how the article as written would lead the public to believe that the Gimlets (my battalion) were “as fine a bunch of men in the whole war, and the story of A Company bore that out.[“] However, admittedly I too am looking at the article in a nonobjective and parochial manner.

Well, the chapter is closed on this episode, but to me there were some worthwhile lessons.

— Always try to find out the background of a reporter that will visit you or your unit.

— Anticipate and look for not only the good news, but also the bad news. This should be done on a continuing basis and not just when a reporter is visiting you.

— When a story breaks, be prepared to react. The reaction should be honest and factual. It should be a maximum disclosure and given rapidly. The public knows that no one is perfect, especially an organization as large as an army. While there may be some initial embarrassment, it will quickly fade away. Any attempt to cover up or distort the facts will only draw more attention to the issue, and as we all know, the truth will eventually be brought to light.

***

I’ve written several blogs about the episode from soldiers who were there. One was an interview with Alpha Company medic Fred Sanders. Another was an account by artillery officer Alan Freeman, and another by company “grunt” James Dieli. All maintained there had been no mutiny.

Bacon lived to see my book on my cousin, Warrant Officer Nicholas L. Venditti, which was titled Tragedy at Chu Lai and published by McFarland & Co. in 2016. The next year, Bacon died from cancer at 83. Here is his obituary.

He had once written: “I know your book is a labor of love, but you have probably gotten much more out of your efforts than just a book.

“I am sorry I’m a little sketchy on the details, but what I did tell you is 100% true. Thankfully because of the grace of God, many of the bad experiences, injuries, etc. are hidden deeply in our brains. For example, it is difficult to remember the pain of a serious injury. Were it otherwise, I think more of us would have gone mad.”