During World War II, Max Snider provided the gasoline for tank commander George S. Patton’s army in Europe. Twenty-six years ago, the freelance writer and retired associate dean of Lehigh University’s College of Business and Economics sent me this story he wrote. It’s about his role in clearing a soldier’s marriage after the war had been won.

—

(Newspapers.com)

In about mid-September 1945, I found in Army mail brought to my battalion headquarters in Liege, Belgium, orders that the Army had appointed me to interview a young Belgian woman living with her mother, a widow, on a small farm a few miles outside Liege. An American soldier had requested the required Army permission to marry the daughter. These orders demanded that I fill out an elaborate questionnaire, designed by some Army personnel type, and make a mandatory decision as to whether I would recommend approval or disapproval of the marriage. The soldier’s Army record was detailed. He was 21 years old and had served as a private first class infantry rifleman who landed on D-Day in Normandy at Utah Beach, fought his way through the campaigns of Normandy, Northern France, Ardennes (Battle of the Bulge), Rhineland and Germany and somehow managed to suffer only two minor wounds. I marveled at the awesome control of our Army over this soldier — to intrude into the most intensely private and personal issue of approving or denying his marriage.

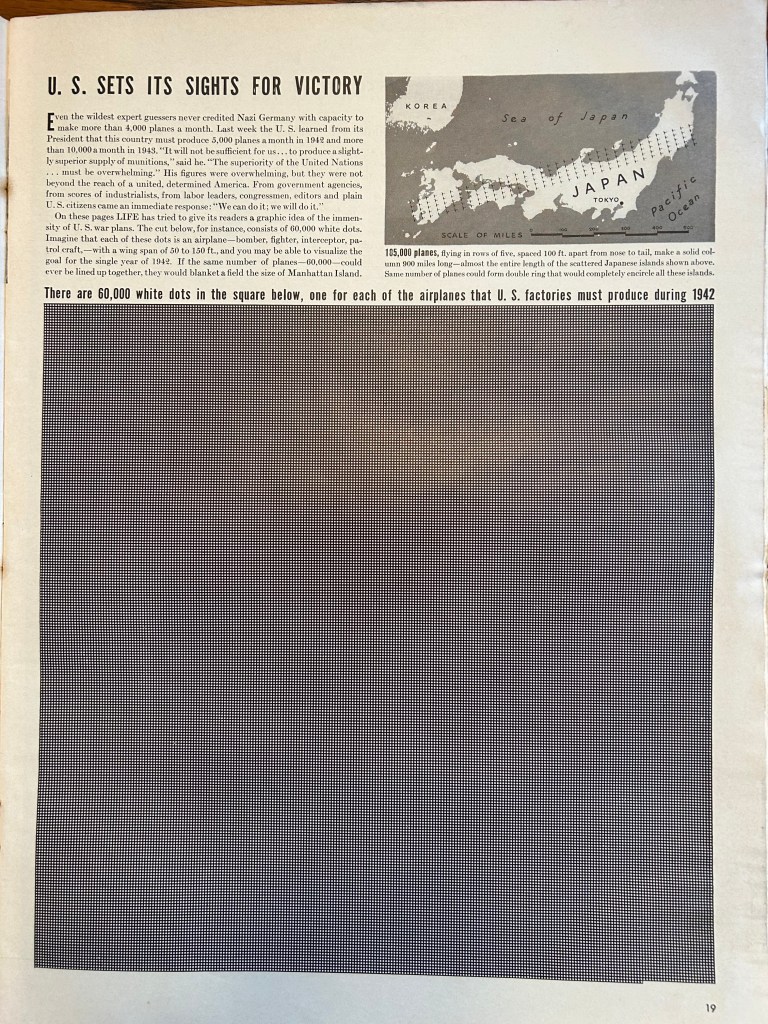

At this time, I was a 30-year-old lieutenant colonel in command of a battalion headquarters. I had served in the headquarters of General Patton’s 3rd Army in charge of gasoline through the campaigns of Normandy, Northern France and Rhineland. It was my job to travel by jeep from the 3rd Army headquarters to as near the front lines as we dared to set up gasoline dumps and supervise their operation. The United Nations had won the war in Europe and in Japan. We waited impatiently to return home. The horrors of the war were still fresh in my mind. In my nightmares, I re-enacted them — the ancient stone houses of Sainte-Mere-Eglise in Normandy that had housed many generations of French families reduced to rubble, the wan and hungry children, the dead soldiers and the dying soldier crying for his mother in an Army hospital during my 10-day confinement there in Nancy, France.

The Army furnished me with a staff car and driver and a translator who could speak the French dialect of the Belgian Walloons and turn it into heavily French-accented English. The translator, skinny, poker-faced with a cadaverous complexion, smoked a huge pipe almost as big as a saxophone. He had stuffed his pipe with a minimal amount of tobacco, still in short supply in Belgium after the war, but if you judged from the odor of his pipe, the biggest portion in his pipe bowl was dead leaves. I dreaded this whole operation, especially asking all the personal questions. One of them even asked the bride-to-be whether she was pregnant.

Our driver drove us to a modest cottage in the center of four or five acres of farmland. A basket of apples and two pumpkins rested just outside the front door. A light rain had stopped, and the sun came out just as an apron-clad and apprehensive farm wife answered the door. The translator told me that she was expecting us and knew why we came.

In an effort to ease the tension, I remarked, “I’m glad you turned off the rain for us.” She managed a feeble smile and introduced her equally fearful daughter, a beautiful young woman dressed in a simple blue dress accenting her blue eyes. My voluminous instructions had told me she was 18 years old. Her innocent and shy demeanor left me ill at ease when I thought of the questions I must ask her.

During the long process of questioning, slowed by the necessity to use French, both mother and daughter sat nervously on the edges of their chairs. I learned both of the young people grew up on farms and that they planned to live with the soldier’s parents temporarily on a large farm in Iowa — the translator pronounced it “E-oh-wah” — until they had their own house.

Finally I came to the question I dreaded to ask: Is the soldier’s fiancee pregnant? I instructed the translator to ask the young woman to step out of the house until he told her to return. When she was gone, in an atmosphere thick with suspense, I posed the question to the mother. She shook her head vigorously in the negative. When the bride-to-be returned with a mystified expression on her face, she immediately asked her mother what the question was. The translator, in a stage whisper, relayed their conversation to my ear. After the mother told her the issue was whether or not she was pregnant, both women burst into laughter and shook their heads to indicate “no.” Then the mother, who suddenly seemed more relaxed, more talkative and all smiles, described how much the couple loved each other and how happy they were together.

“If you could see them together,” she said, “you would know they are very much in love.”

“I will strongly recommend approval of this marriage,” I told the mother and daughter. They laughed and embraced, and the daughter began to cry.

Reluctantly, I told them that a higher Army headquarters could overrule my approval.

“When will we hear the final outcome?” the mother asked.

“From my experience in this Army,” I replied, “it is not noted for speed in its paperwork.”

After the pleasant ending of the conversation, I left in high spirits indeed. In a world that had started two ghastly world wars only 25 years apart, this brave soldier could look forward to peace with his beautiful wife. During the drive back to Liege, I fantasized about this couple who would live on that big farm in Iowa. Their children would be bilingual, learning French from their mother and English from their father, and, of course, some of them would be blue-eyed like their mother.

The End

—

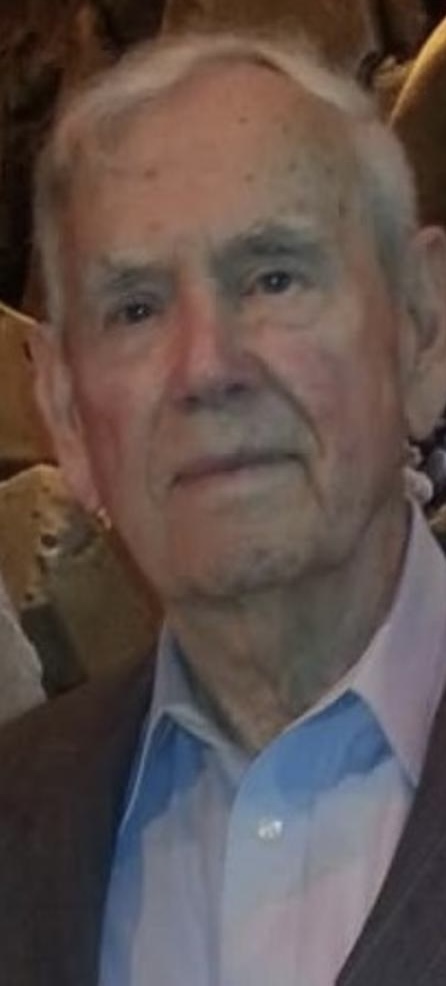

Snider stood out in both the military and education. An Illinois native, he earned master’s degrees in advertising/marketing and business administration. From the Army’s Reserve Officer Training Corps, he became a second lieutenant of cavalry in 1936. In Europe with Lieutenant General Patton’s headquarters, he rose up the ranks from first lieutenant to colonel. Three decades of service in the Reserve followed. At Lehigh University for 34 years, he was a professor and dean and co-wrote four books. Later, as a freelancer, he wrote his memoirs. He lived in rural Durham Township, Bucks County, where he died in 2012 at age 97. You can read his obituary here.

Snider sent me his “marriage approval” story in 1999 while I was working at The Morning Call of Allentown. When I retired, it came home with me along with other war stories that were offered to the newspaper but not published.