World War II veteran Stan Friday grew up in the Philadelphia area, the eldest of 10 children. He attended Lower Merion High School and worked at a factory that made gasoline cans for the war effort. In October 1942, he was drafted into the Army.

After training in Kansas and Arizona, he shipped out to Scotland aboard the Queen Mary with 18,000 other soldiers for the invasion of Nazi-occupied France.

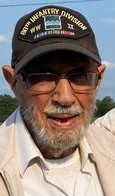

In the first week of August 1944, less than two months after D-Day, he came ashore at Normandy’s Utah Beach with the 80th Infantry Division. He fought the Germans across Europe as a 22-year-old scout in the 317th Infantry Regiment.

IN HIS OWN WORDS

I was a private in General Patton’s 3rd Army. From Utah Beach, we went into every little town, cleaned the town out and went to the next town. Every town you went into, they were glad to have you.

My job was to fight if I had to — I carried an M1 carbine, a .45-caliber pistol and grenades — but going behind the lines to get information was my specialty. I collected half a dozen prisoners for interviews. Most of the time, I went out alone. Sometimes I went with a carrier who’d carry messages back to the lines when we’d run into something. I got close enough to the Germans to see them, hear them, smell the stinkin’ cigarettes they were smoking in their foxholes. You could smell them a mile away. That was a giveaway.

I could handle myself pretty good. My dad was a boxer, so he taught all of us boys how to take care of ourselves. We all had a pair of gloves. I started when I was 2 or 3 years old, so I was pretty rugged that way.

Scouting was nighttime or daytime, depending on the situation. If you knew there was a whole bunch of Germans in one area, our commanders wanted to know about how many. Our job was to go out there, be visible and get shot at, and get away and report back.

I moved on instinct, training. Everything happened so fast. I was fightin’ to save my life, No.1, and trying to outwit the Germans. I was kind of foxy, watched where I went. My night vision was extraordinary. That was before they had glasses today that you can see with in the dark.

Was I ever spotted? Yeah, because somebody was shootin’ at me. It was half moonlight, half just getting light. I seen a German up in a big building. There was one shingle missing and a rifle. Light must have hit it and made a glare, and I seen a flicker in it, and I go: There’s a sniper up there. And I just snuck away, hit the edge of a building and dove through the building. The only thing that didn’t make it was the heel of my shoe. He shot it off. Didn’t hurt my foot. I’m glad I got away.

What am I doing here? I’d think that. But after a while you forget it, and you just continue what you’re doing.

The Sherman tanks and the German Mark V’s had a big battle going on at St. Lo. I found a hole, a depression in the ground, and I just threw myself in it to get away from the firing and covered my face with my arms. A shell from a German tank went off near me. It made me deaf, and I got shrapnel in both arms. Blood was running down. I patched it up myself. Them scars are still with me.

If somebody was shootin’ at me, I shot back. Did I hit anyone? Damned if I know. I could’ve. You didn’t have time to look around and see if you hit anybody.

I was usually with my buddy. His name was Monday, and I was Friday. His first name was Kenneth. We were like brothers. We were friends from the day we got in. He was from Wheeling, West Virginia. He got killed in France. I think he got hit when we were around Metz or Nancy.

He took one patrol out, I took another patrol out. Somehow he got caught by a German 88 [millimeter gun]. They caught him comin’ down the side of a hill outside a little town. He got hit in the side. The last thing he told the medic, he wanted to know if I was all right. It was a week later, two weeks later that I found out what happened to him. We were in such commotion there, nothing but fighting and noise.

I don’t want to talk about the Battle of the Bulge. That’s gory. It would put me in a bad mood.

We went in every little town up to Austria. When we got there, we found out the war ended. Austria was like a vacation. Sat around, went swimming, boating, just waiting for a boat to take us home. We waited until October ’45.

At home, I was a wreck. I had nightmares. I couldn’t sleep at night. I got arrested for bein’ bad, drinkin’, gettin’ in fights, startin’ trouble. I loved trouble. The cops said, “We don’t want to see you here again.” It was the transition from Army life to civilian life. Guys couldn’t cope with it. They didn’t know what it was. I seen guys commit suicide and get divorced from their wives. Doctors then didn’t have an idea until they found out it’s in the mind. They had to bring them down on pills and dope.

Not me. I said, I can’t go on living like this. I got hold of my senses and after a while, I straightened out. I went down to Willow Grove [the naval air station] and joined the Navy to get used to civilian life. I could wear civilian clothes. I had training to keep the planes in operation. After about three-and-a-half years, I had to come out. My mother was having a rough time, so they let me out early.

I’d wanted to forget a lot of stuff, and I did a good job of it by joining the Navy.

I got into the construction trade, and I liked construction pretty good. I worked hard at it and learned all I could, worked all the way up to a foreman and then to a superintendent. I was a superintendent of construction for 37 years. I worked on the Limerick [nuclear power plant] towers, the two towers. They’re my babies.

EPILOGUE

For this interview, Friday would not talk about the time a German soldier came at him with a bayonet and the fighting was hand to hand.

“I shudder every time I think about it,” he said. “I don’t want to get into that. It’s stuff I don’t want to even think about. It gets me worried. I’m trying to get the hell away from the past! I don’t want to lay in bed and start crying.”

He did say the tip of the blade made contact with his chest but was blunted by the webbing of his carbine.

Friday was honorably discharged Octpber 21, 1945, at Indiantown Gap. At the time, he was a technician fifth grade, or “tech corporal,” with Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 317th Infantry Regiment, 80th Infantry Division. He had fought in France, Luxembourg, Germany and Austria. Among his decorations were the Purple Heart and Bronze Star.

He worked in construction until retiring at 65. In two-and-a-half years, he designed and built a house on Ziegler Road in Marlborough Township, near Pennsburg. “It’s still standing, a beautiful house,” he said. At the time I met with him, he was living in the Souderton area.

He and his wife, LaRue, went to France for the 75th anniversary of D-Day on June 6, 2019. (Here’s an ABC News article about him.) Honored as a participant in the Allied invasion of Normandy, he shook hands with President Donald Trump and received the highest decoration awarded by the French government, the Legion of Honor, from President Emmanuel Macron.

While presenting the medal during the Omaha Beach ceremony, Macron told Friday, “I’ve read your information, and I know what you did for France.”

Here is Friday in a video interview for the Bastogne War Museum, a brief interview with David Muir of ABC World News Tonight, and an interview with two other Normandy veterans on CBS This Morning.

Friday died December 28, 2025, nine days after LaRue’s passing. He was 103. Here is his obituary.

—

My friend Sharon Schell, a booster of veterans, told me about Friday. Her late father, Charles F. Remington, had fought across Europe in the 94th Infantry Division. In 2016, my last year at The Morning Call of Allentown, I got his story into the paper.

Sharon took me to interview Friday on July 3, 2023, at his home. I planned to offer the story to The Morning Call and wrote a draft, which you have just read. But 10 days after our meeting, before I could have a follow-up interview with him, Friday backed out.

A friend said Friday didn’t want to talk anymore. He was having nightmares. He just wanted to forget.