“As a noncombatant combat medic, I experienced seeing much suffering, ruthless cruelty and tragedy in Vietnam,” Fred Sanders wrote to me. “For those who have experienced or witnessed traumatic events in their lives, I would counsel: Do not nurse your pain. It will only prolong the suffering and make your life more difficult.”

Sanders is 78 and lives near Columbia, South Carolina. He was with the Americal Division unit involved in the reported mutiny of U.S. troops in 1969. Last year, I blogged his account of “the very unfortunate thing that was not a mutiny.” Today, I’m sharing more of his Vietnam story, as he has told it to me.

I became a medic because I was a conscientious objector. I did not want to kill. I was well read on world affairs, politics. I saw then what people now recognize as the truth of what happened in Vietnam.

But this didn’t figure in my C.O. position. I felt it best to serve as a noncombatant on religious grounds. I belonged to a Baptist church, and the Southern Baptist Convention recognized my personal convictions as a C.O. My best choice was to try to save as many lives as I could.

I was a student at the University of South Carolina, interested in getting a degree in biology. I stayed out one summer to work for the state engineer’s office to make money to get back into college. But I didn’t get back in the first semester because I missed signing up.

A draft board member heard I stayed out a semester, and they pulled my name to be drafted. I said I’d like to register as a C.O. I wasn’t trying to get out of the Army. I said I’d go as a medic.

The head of the draft board got angry. He said, “You’re gonna put a black mark on Aiken County’s history.” I said I’m not asking for alternative service like Mennonite friends of mine. I’ll do the best I can if you let me serve in a medical capacity and try to bring some of these young men home alive.

—

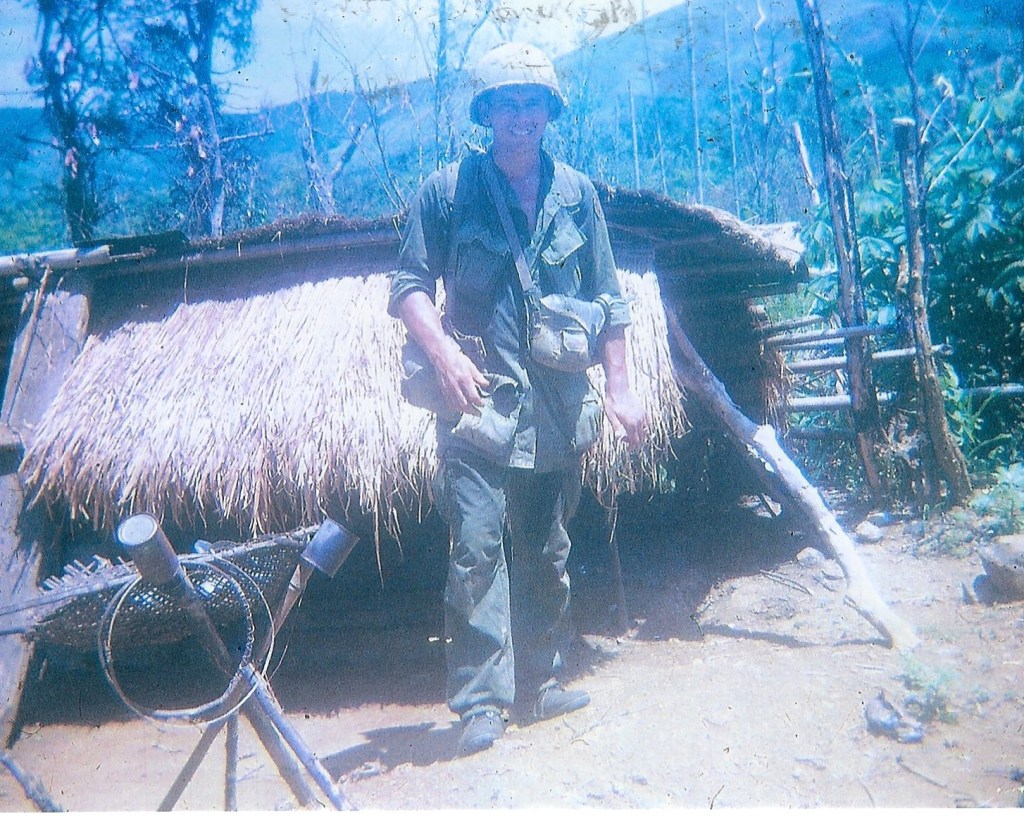

“I had a lot of experience dealing with people dying,” Sanders said of his year in the northernmost U.S. military zone of South Vietnam. He was 23, 24 years old while serving with Alpha Company, 3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry Regiment. “They called me an old guy.”

In the Song Chang Valley south of Da Nang, a friend of his, Sergeant Derwin Pitts, was shot as they walked down a hill toward the enemy. He lay groaning about six feet away, his position exposed. Sanders tried to figure how he could reach him without also being shot. Just then, Private First Class Ray Barker called him off, saying, “Doc, you’re not gonna do it.” He crawled past Sanders toward Pitts and was immediately killed. Pitts also died where he lay.

Another time, a young man was hit by a fragment from an antipersonnel artillery round. “That metal had severed his throat. He was hemorrhaging in his mouth, and I had to try and clear his airway but was unsuccessful. I was sucking blood out of his throat. There was nothing I could do to save him.”

Some men had self-inflicted wounds, “which I suspected of stemming from fear of being killed.” One shot himself in the foot. On another occasion, Sanders had just spoken with a man who was cleaning his M16 and heard a shot fired. “I ran to him and found his leg hanging only by skin. He said that the trigger caught on a root. He had expressed fear of being killed when walking point on patrol. He insisted that [the shooting] was an accident.”

Atrocities happened, and Sanders witnessed a few. He was with a platoon when they came across an old Vietnamese woman carrying a bundle of ruled notebooks and about $20 in Vietnamese money. She lived in a little grass shack with two children about 10-11 years old. The platoon leader, a lieutenant, called battalion commander Eli Howard and asked what to do with her. “I don’t want any prisoners,” Howard said. “All I want is body count.” The lieutenant said, “OK, sir,” and turned to the men. “All right, fellas, I need somebody to get rid of this woman.”

What! Sanders thought. You’re going to execute her? That’s a war crime! What had she done?

“Somebody do it,” the lieutenant repeated. There were at least 10 men standing around. Everyone looked at one another, said nothing, then looked down at the ground. One soldier finally spoke up. “I’ll do it,” he said. Everyone stood back.

The two children were with the woman. She was hugging them. The soldier put his rifle to her head, fired and killed her. The children screamed and ran off into the jungle. Sanders said two men from the platoon went into the bush, perhaps to pursue them. He heard that members of a nearby platoon chased down the children and killed them to make sure there weren’t any witnesses.

“Nobody wants to remember this,” Sanders said. “It left a lot of bitterness with some of us. There was certainly no military value in it.”

Did Sanders speak up about what happened?

I was thinking I can’t say anything because it would put me in a very bad position. I’d had a long experience with taking an unpopular stand, though not with this platoon.

When I was attached to another company earlier, one day a helicopter came and in and they said, “We’re taking you back to LZ Center,” the battalion command post. They told me privately that someone reported “there’s a plot to shoot you during a firefight. Some of these guys want you out of the company, because they don’t appreciate you giving out little Bible tracts in Vietnamese to the people. They resent you. We’re getting you out of here for your own safety.”

When I was in Taipei, Taiwan, I bought a very nice professional camera. I was at the canteen at Chu Lai [the Americal Division base], standing at the counter, and there were some guys at a table and they started talking to me, and when I turned to them, they sent somebody around to my other side where my camera was, and he stole it. They were afraid I might take pictures of something that might get them in trouble. But I never considered doing anything to besmirch my men or the unit in general.

Sanders said no one reported the old woman’s murder to the higher-ups.

We dared not go that far with it. I didn’t think at the time that the leadership culture would want it uncovered. That was bad publicity. It would expose the brigade to public scrutiny at a time when mixed public sentiments were influencing conduct of the war.

Also, for my own safety, I had to be careful. I was quite aware of the environment I was in. I’m here with a group of men. I don’t know what their life was. They could’ve been gangbangers before they got drafted.

Sanders said that on a previous occasion while the platoon was on patrol, a soldier shot an old man leaning against a betel nut tree near a cluster of huts, blowing the top of his head off. “What did you do that for?” Sanders asked him. “I panicked. I saw that man, and I didn’t know what to do.” After that, Sanders kept an eye on him and asked him now and then how he was doing, thinking he might be shaken by what he’d done.

“To the best of my remembrance, he was the same guy who shot this woman.”

After killing her, he asked Sanders: “Doc, do you think maybe you could write me up and get me out of the field? I don’t feel like I’m doing too good.”

“I filed a medical recommendation to remove him from field duty as possibly having combat-readiness issues. … I don’t know what became of him,” Sanders said.

Recently, a friend who’d been in the platoon told Sanders that the soldier “admitted to some of us” he shot the woman to get out of the field – a revelation that shocked Sanders. The soldier wanted to manipulate the medic into writing a recommendation that he wasn’t stable and should be removed from field duty.

—

Sanders said the lieutenant who asked for a volunteer to execute the old woman once allowed several of his men to rape a Vietnamese girl. Sanders was with the platoon and didn’t see the assaults but was aware of them. He described the girl as pretty and nicely dressed for someone in the jungle. The lieutenant, he told me, “was totally unwilling to take charge of his men.”

I was with another company one time, and we had walked into a hamlet, and this guy said, “All these people are V.C. [Viet Cong], and he started shooting. He killed men, women and children – 12 or 14 people. Everybody was in shock, but everybody kept their mouths shut, because all of these guys [I’m with] have arms, and you just don’t want to cross anybody, because people can be very dangerous and there aren’t any rules, unless a commander intervenes. Six weeks after that man killed all those people in that tiny hamlet, one of the guys came to me and said, “Doc, he got justice. He got what he asked for.” He had been shot and killed in a firefight.

Once, Sanders was riding in a helicopter with a prisoner and a soldier who carried a Bowie knife and was known to kill detainees. “First thing I know, he shoved the detainee out of the helicopter and said, ‘Oh, he slipped and fell.’”

“It was a great challenge to me to go through all this.”

—

How did Sanders keep his head?

I read 24 books in the field, every time we had a break and we were not in danger. Reading is good medicine. It put me in another place.

My faith in God sustained me.

I maintained friendships with as many people as I could.

For some years after I came back, PTSD really hit me. My wife would go to bed and I’d sit in the kitchen and cry, remembering all the suffering and death that I had witnessed.

One night as I was sitting there, my wife said, “Why don’t you come to bed?” I said I’d be there soon, and she fell asleep. I heard a voice in my head: “I would heal you, but you have never asked.” I said, “Huh, what?” I realized it was the voice of God speaking to me in my mind. I was so moved and humbled and asked forgiveness. I said, “Lord, heal my memory.”

From that day on, I never again sat up in the kitchen at night crying. I’m able to sleep.

I still have dreams of being in evasive tactics in Vietnam but never seeing anything violent. One night I dreamed I was in an underground bunker with the North Vietnamese, and I saw their life in the bunker, and I’m watching all these North Vietnamese walking around. When I woke up the next morning, I said: My goodness that was real! But it didn’t disturb me.

I have had healing of my memories.