First of two parts

The last time I wrote about World War II flier Robert Harvey Riedy was seven years ago. Now someone wanted to talk to me about him. An editor at my former employer, The Morning Call of Allentown, Pennsylvania, emailed a transcription of a voicemail message. I didn’t recognize the man’s name. He left his phone number but didn’t say where he was calling from.

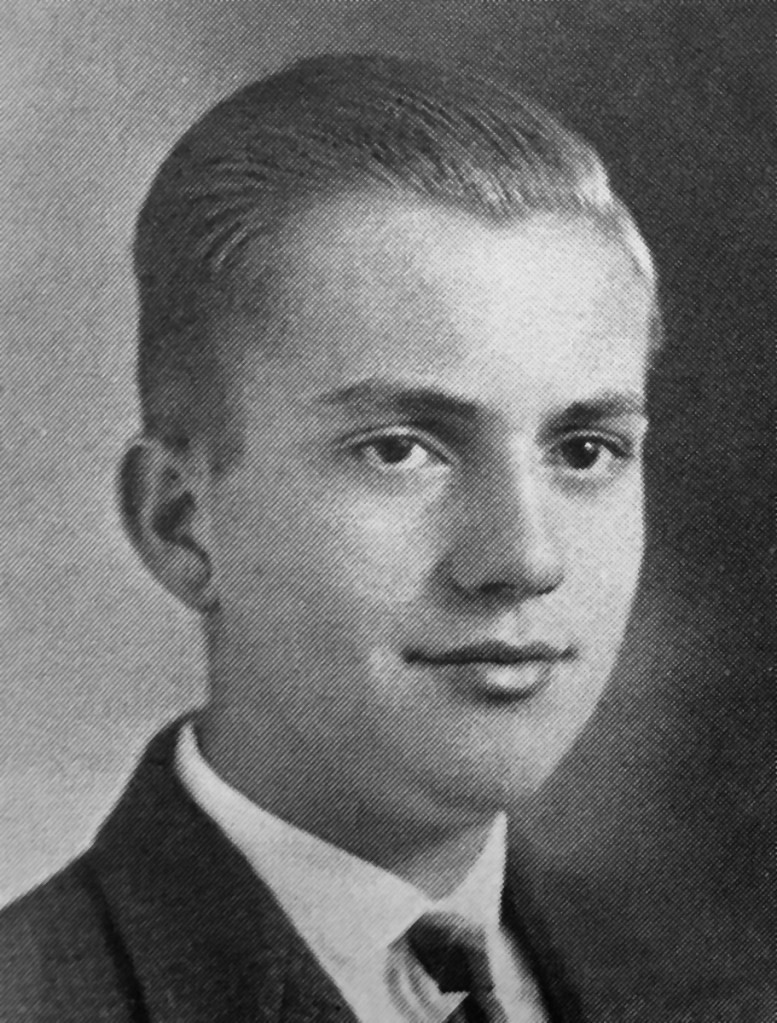

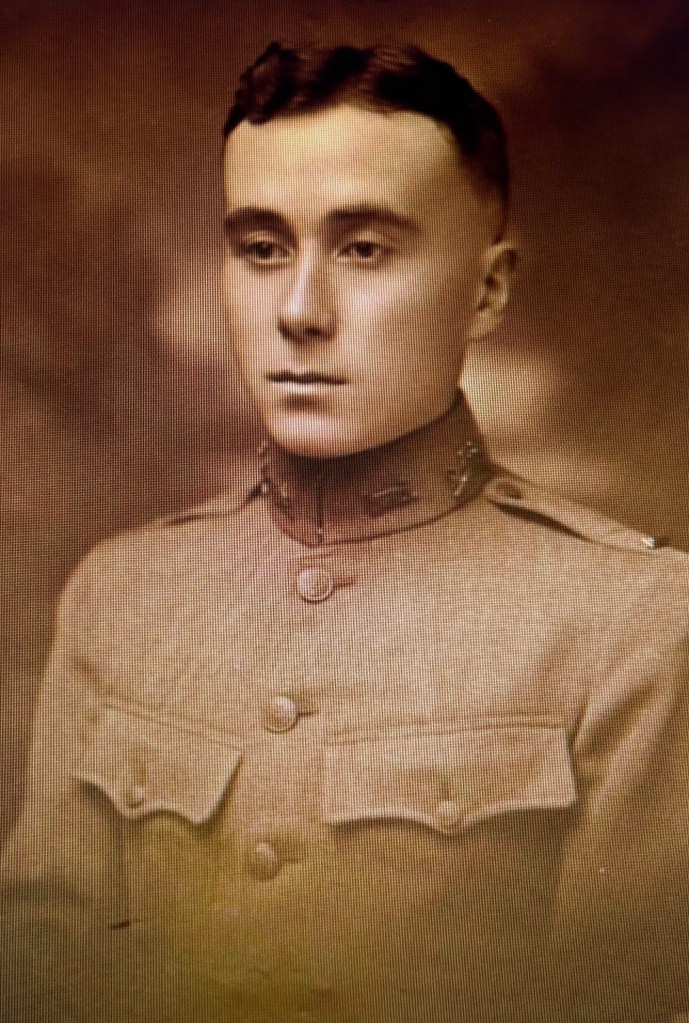

Riedy was a 1938 Allentown High School grad memorialized as the first serviceman from the city to die in Europe during the war. My file on him was more than 2 inches thick. What more was there to learn about him?

—

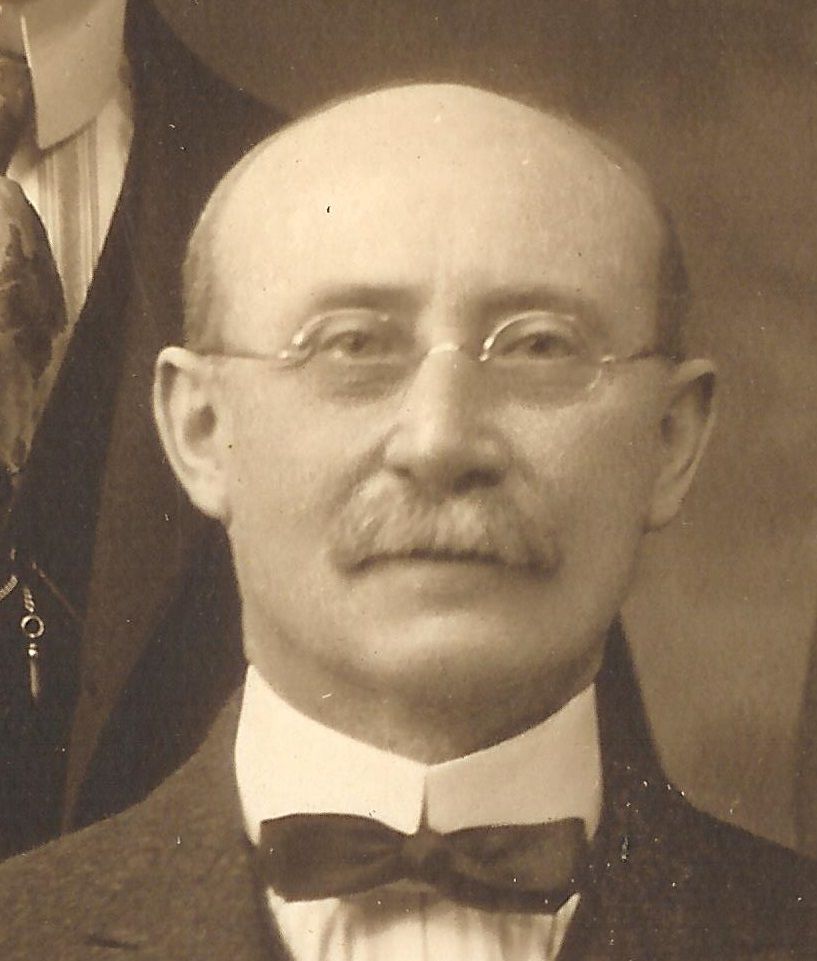

Bob Riedy was a YMCA summer camp leader and a swimmer, the only child of Harvey and Eva Riedy of Jackson Street near the Little Lehigh Creek. His dad was a cashier and freight agent for the Jersey Central and Reading railroads and a leader in the local Democratic Party.

Bob’s teachers and pals at Allentown High described him as brilliant. The yearbook says he “has good common sense and good judgment. … Because his mind is usually wandering around in the air, he is planning for a career in aviation.”

He graduated with honors at sixteen and followed through on his plan, studying aircraft maintenance at the Curtiss-Wright Technical Institute in Glendale, California. In April 1939, he made headlines across the country when he caught a ride home with a noted transport pilot, Frank Cordova, on a twin-engine Barkley Grow. Bob’s hometown newspaper crowed that he “contributed to the log of American aviation by being recorded as the first trans-continental hitchhiker through the clouds.”

After 14 months at Glendale, he found work at the Consolidated Aircraft Corp. in San Diego. Then in April 1940, he was hired as an aeronautical engineer at the Curtiss-Wright plant in Buffalo, New York, one of the largest airplane factories in the world, where he worked alongside college graduates.

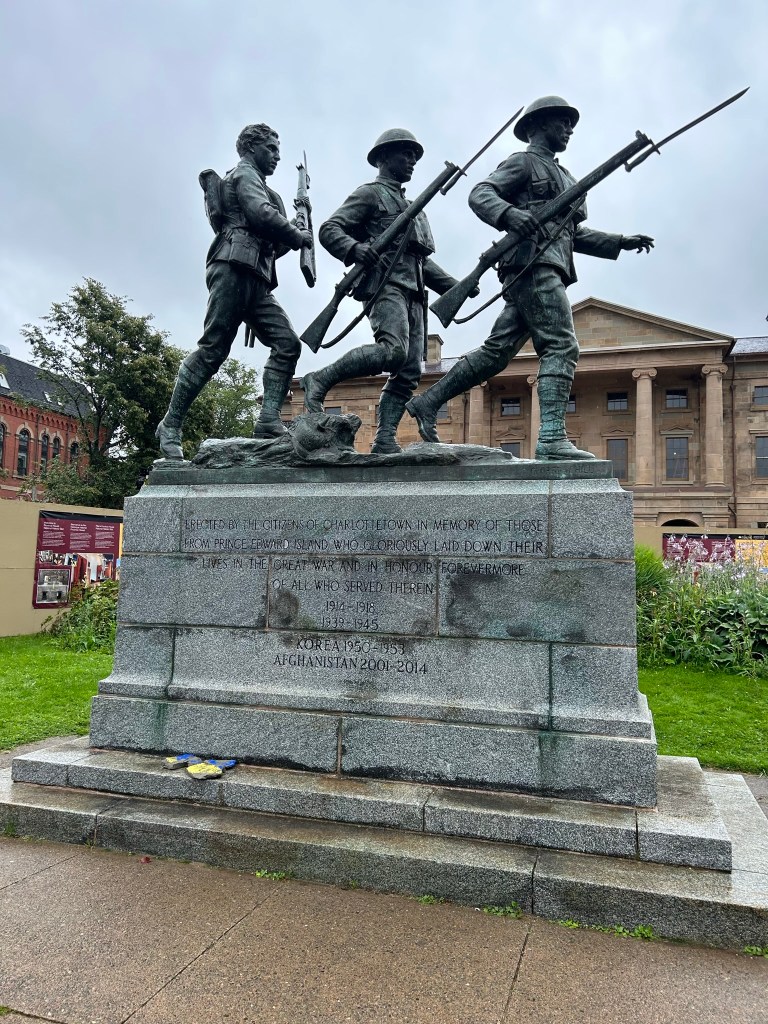

Bob wrote to his parents from Toronto seven months later. He had quit his job and flouted U.S. neutrality by crossing the border to join the Dominion of Canada in the fight against the Nazis.

“I am in training with the Royal Canadian Air Force under the British Commonwealth Training Plan as a ‘special reserve,’ ” he wrote on December 13 from No. 1 Manning Depot. “After the completion of about eight to nine months’ training, I expect a commission as pilot-officer. … If they don’t give me a commission, I shall at least become a sergeant-pilot.”

His joining the RCAF hadn’t been “as sudden and impetuous as you may think,” he wrote to his buddy Charles Fegely in Allentown. “I had been contemplating it for some time. … For years I had cherished hopes of getting into the Royal Air Force. … This may sound a bit unpatriotic to you as it does to all my other friends, but … the RAF with its squadrons all over the world from Cairo to Singapore spells just a little more romance than ‘U.S. Army Air Corps.’ “

On December 17, 1940, he wired his parents that he was being transferred to Coastal Command and would be leaving the next day for RCAF Station Debert, Nova Scotia, a training site for pilots and aircrew from British Commonwealth nations.

“I hope to become a writer someday,” Bob told The Morning Call when he was home for Christmas. “My experiences now should help me considerably.”

Returning to Canada, he took air navigation courses at No. 3 Initial Training School in Victoriaville, Quebec. After that, he was off to No. 2 Elementary Flying Training School at Fort William, Ontario, and then to No. 6 Service Flying Training School at Dunnville, Ontario.

In October 1941, Sergeant-Pilot Riedy ferried a bomber to England. “Arrived safe – having swell time,” he said in a cablegram to his parents. But in a letter to Charles Fegely, he made clear his disappointment: “In spite of the fact that I expected to fly fighters, they’ve stuck me on bombers.”

According to his RCAF service record, he was assigned to No. 20 Operational Training Unit at Lossiemouth, Scotland, which trained night bomber crews using the twin-engine Vickers Wellington. An OTU was the crews’ final training stage and included operational sorties.

On December 7, 1941, the day of the Pearl Harbor attack, Bob wrote to his YMCA friends at home that he had gotten out of flying bombers. “It was just like driving a truck, so I raised a stink – told them that my dad was a good friend of FDR and all that. It worked, and I’m being put back on fighters, which are a heck of a lot more fun.”

Bob’s service record doesn’t show him with a fighter unit. It has him remaining with No. 20 OTU until February 1942, when he was transferred to No. 15 OTU at RAF Harwell, which provided the same bomber training.

In his letter to his YMCA pals, Bob wrote about how grateful he was to the British servicewomen who kept him safe in the skies.

“Whenever the weather sets in and you get yourself lost (which is practically always with me) it’s invariably a woman control officer who gets you down in one piece and on the right side of the [English] channel. …

“Perhaps you think I’m eulogizing them too much, but when your life depends on them every time you take off, and when some 18-year-old girl, who is much more homesick than you are, fixes a jam in your guns in a hurried refuel – well, you want to let somebody hear about it.”

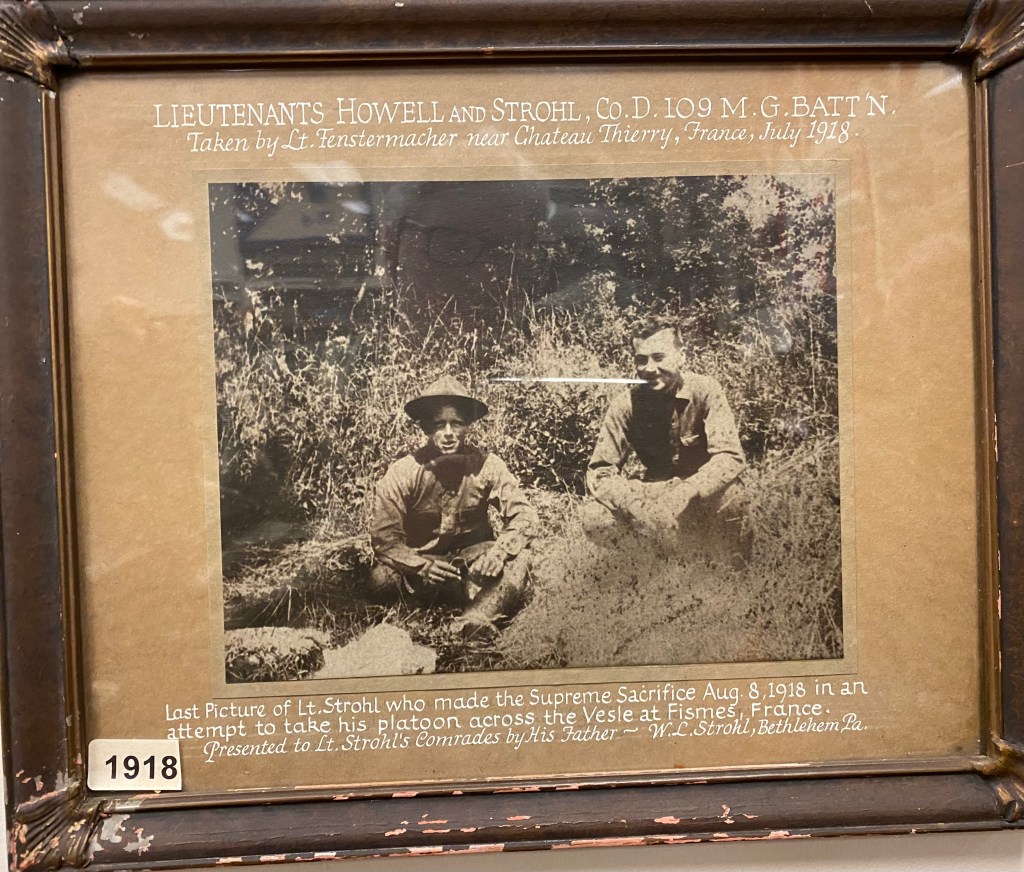

No British servicewoman or anyone else would be able to save him one day at an airfield near Oxford. He wouldn’t live to become a writer, but he wasn’t forgotten. Eighty-one years after Bob’s death, medals he earned were returned to his hometown for display in a place of honor. It happened after I called the man who wanted to talk to me about him.

COMING NEXT: A proper home for Riedy’s medals