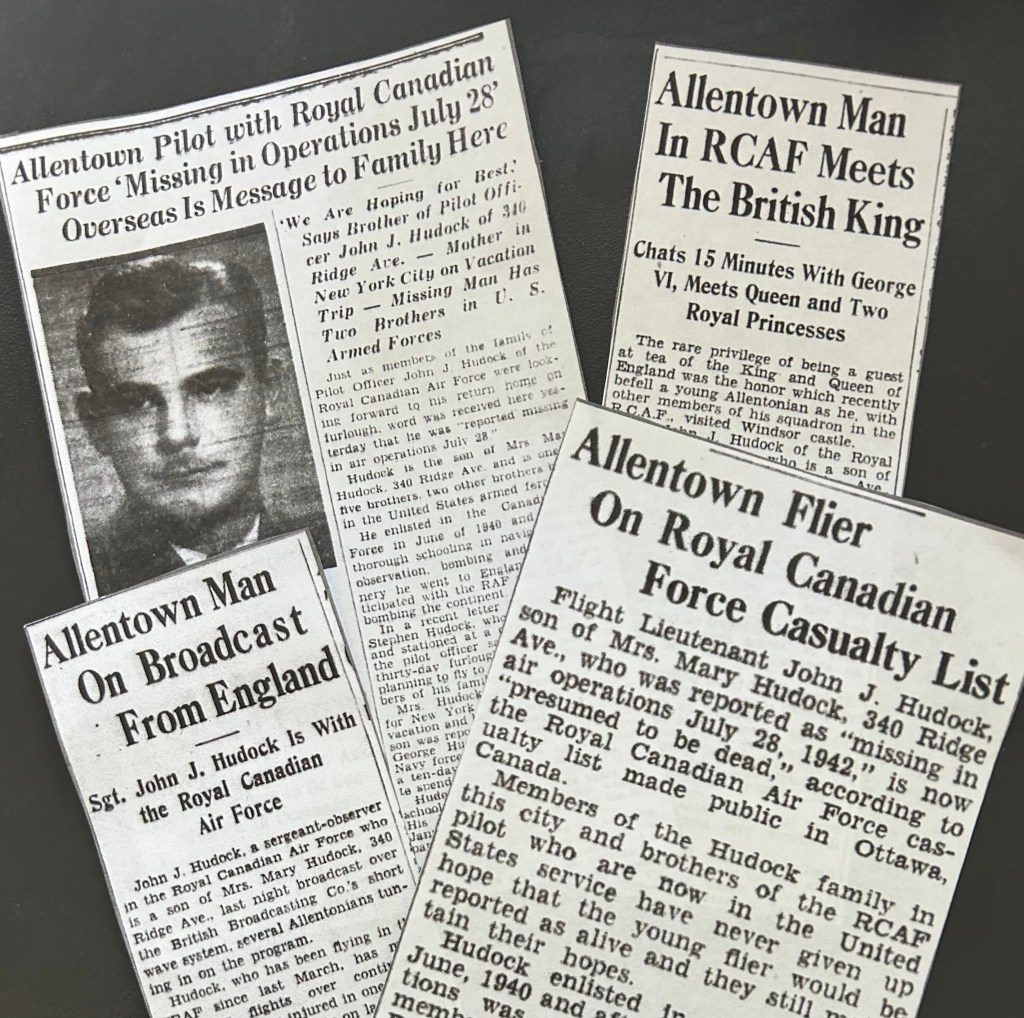

It’s the spring of 1916, and there’s talk of war with Mexico. National Guard troops leave Pennsylvania to protect the border. One of their officers is the city editor of The Morning Call in Allentown, who aims to keep the folks back home informed. Captain Clarence J. Smith, quartermaster of the 4th Infantry Regiment, sends stories about how the soldiers geared up for duty and managed camp life in the west Texas desert.

The Guard call-up stemmed from a March 1916 raid on Columbus, New Mexico, by Mexican bandits under Pancho Villa that left 17 Americans dead. President Woodrow Wilson ordered a punitive expedition led by Brigadier General “Black Jack” Pershing and sent more than 100,000 Guardsmen to the border. They included three companies from Allentown and neighboring Bethlehem that were part of the 4th Regiment, 7th Division. (It was reorganized as the 28th Division in 1917.)

The assembly point for the Pennsylvanians was an old cavalry site 32 miles east of Harrisburg called Mount Gretna. Smith wrote his first dispatch after the Lehigh Valley companies and the 4th Hospital Corps arrived there on Saturday, June 24.

The first night in camp … was one that would test the mettle of the most active soldiers. This regiment arrived in camp under a hot June sun and spent the afternoon on Saturday going to work at housekeeping. A total absence of horses and mules necessitated the men carrying all baggage from the troop train, and it was a tired bunch of soldiers, half in khaki and half in civilian dress, that turned in to sleep. …

The spirit of the men in camp in the last few days in the face of absence of clothing, blankets, etc., with its soggy tents and muddy fields, is most commendable, and every detail for duty is responded to with alacrity.

Several days later, Smith wrote:

Orders were received at noon by the medical officers, and immediately all were at the hospital to rush vaccination of the men and the inoculation against typhoid fever. … All of the men stood this ordeal with fortitude. …

Much of the time Sunday and Monday was occupied with putting the camp into the best sanitary condition, and it fell to the lot of many a “rookie” newly enlisted man to wield a pick and shovel while other details swung an axe so that the cooks might have the sort of fires that would ensure meals on time.

The mess tents being in use as sleeping quarters for the new men, the members of the regiment line up for mess with their meat pans and tin cups, taking his turn in front of the cooks and receiving the share of the mess.

Everyone is ready when meal time comes, and when the cooks call out “Come and get it,” there are no laggards. The men eat their meals seated about on the sod, and a heartier bunch of appetites it would be hard to find. The ration issue is excellent, and the men are being fed well.

On Saturday, July 8, the men of the 4th Regiment left for El Paso, the Texas town on the Rio Grande. Before boarding the train, as they were drawn up in company formation at their Mount Gretna campsite, a Civil War hero arrived to see them off.

This was Ignatz Gresser, a German immigrant, Allentown shoemaker and Medal of Honor recipient for bravery during the 1862 Battle of Antietam. After serving in the Allen Rifles, a “First Defenders” company, he signed up as a corporal in Company D, 128th Pennsylvania Infantry. He got the medal for carrying a wounded comrade from the field while exposed to Confederate fire. The soldier he saved, Corporal William Sowden, went on to become a Pennsylvania congressman and saw that Gresser received the honor.

The Guardsmen gave Gresser, 80, an ovation.

At Camp Stewart in the desert on the edge of El Paso, the men of the 4th Regiment slept in tents, drilled and marched. Smith wrote for his newspaper in mid-July:

The arrival in camp at 10:30 o’clock Monday night of Harry A. Hall of Company B and Lieutenant Robert A. Barber of Company D with two batches of recruits furnished a lively diversion in the two companies. …There were hearty handshakes and congratulations. …

With the arrival of the recruits, Company B has 111 men in camp and Company D, 103. Several other companies of the regiment have their full quota of 150 men. Easton, Lancaster and Pottsville and others are much nearer the 150 mark than Allentown, though it must be remembered that Allentown has two companies in the regiment, while the other cities excepting Reading have but one company. …

The men of the regiment who have not been detailed on special duty handling the supplies, helping the cooks, etc., have been put to drill under the noncoms and are rapidly picking up the rudiments of what all here are beginning to realize is an exact science. … The handling of supplies is a slow job with the few horses and heavy roads for the motor trucks to plow through.

In mid-September, a Morning Call story probably penned by Smith noted “each day’s program is bringing to the men more of the real soldier’s life in the way of being schooled to withstand the rigors of the march and how to take care of one’s self in the field. Monday, the men of the 3rd Brigade, composed of the 4th, 6th and 8th regiments, hiked off into the desert for a dozen miles equipped for field service and accompanied by the wagon trains. Many men were compelled to fall out of the line due to the heat and fatigue, and were brought back to camp in the escort wagons.”

Months passed without trouble from across the Rio Grande. But on Christmas Day 1916, a tremendous gale hit, “driving the sand before it with a velocity that cut the face like a whiplash and tearing tent after tent from its fastenings and scattering the personal effects of the soldiers broadcast,” according to another Morning Call report probably written by Smith. It was the worst storm the troops faced.

Two weeks later, the Guardsmen pulled out of El Paso and headed north to be mustered out of service.

“Not since the Allentown troops returned from the Spanish-American War in 1898 was there such a demonstration in this city as yesterday, when the local companies of the 4th Regiment returned from Texas, where they had been for nearly seven months,” the paper crowed on January 15, 1917. “Bands played, flags waved, and the crowds cheered as the soldiers marched up Hamilton Street to Twelfth.”

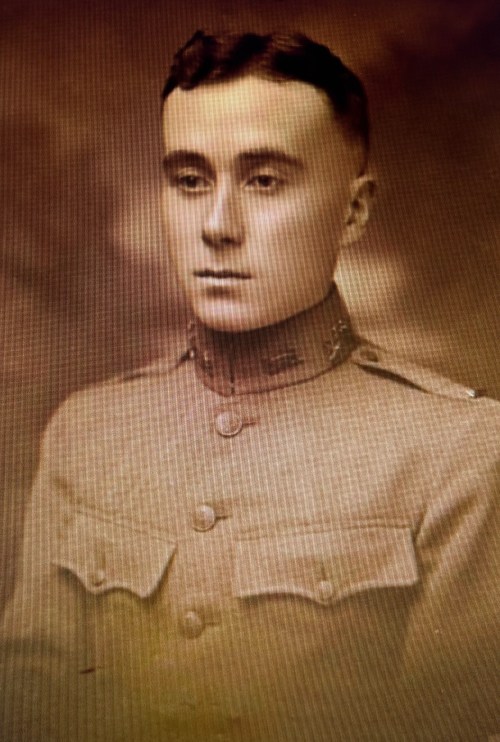

Awaiting many of them was the First World War, which had broken out across the Atlantic two-and-a-half years earlier. Smith would have a role in France as commander of a 28th Division rail unit, the 103rd Ammunition Train. He would go on to become the first commander of the Pennsylvania National Guard’s 213th Coast Artillery Regiment (Anti-Aircraft), descendant of the 4th Regiment.

Born in Easton, Smith had joined the Guard in 1898 after the battleship USS Maine blew up in the harbor at Havana, Cuba, a cause of the war with Spain. He retired as a colonel in 1938 and died two years later in Allentown, revered as an outstanding citizen. The former reporter, editor and publisher was 66.

My main source for this blog is the 213th Regiment booklet Mexican Expedition 1916-1917: History of the Allentown and Bethlehem National Guard, compiled in 2013 by retired Lieutenant Colonel Charles G. Huch. It has contemporary accounts from The Morning Call and the South Bethlehem Globe, and photos from Volume 5 of The 28th Division: Pennsylvania’s Guard in the World War, published in 1923. I’m using some of those photos here, with their original captions in quotes.

Huch was a 1952 graduate of Lehigh University, an Army veteran of the Korean War and a longtime Bethlehem Steel employee. He died on the last day of 2020 at age 92.