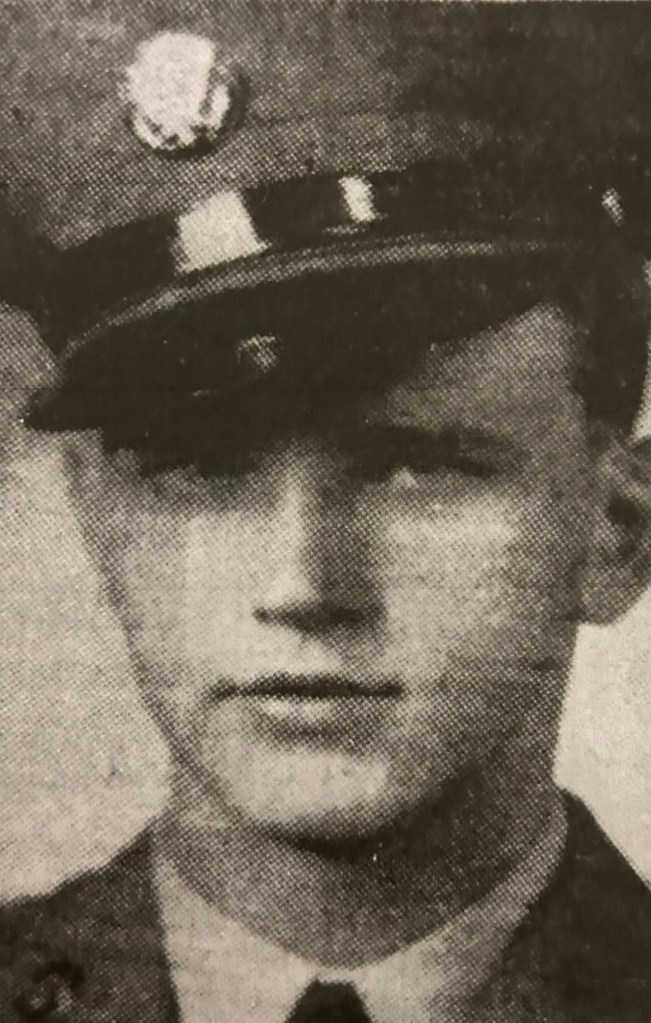

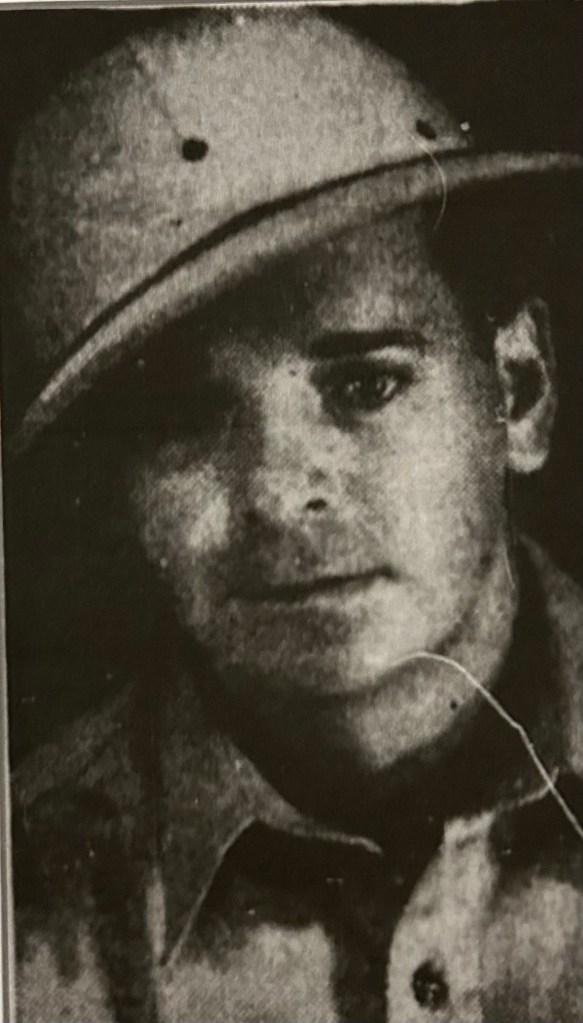

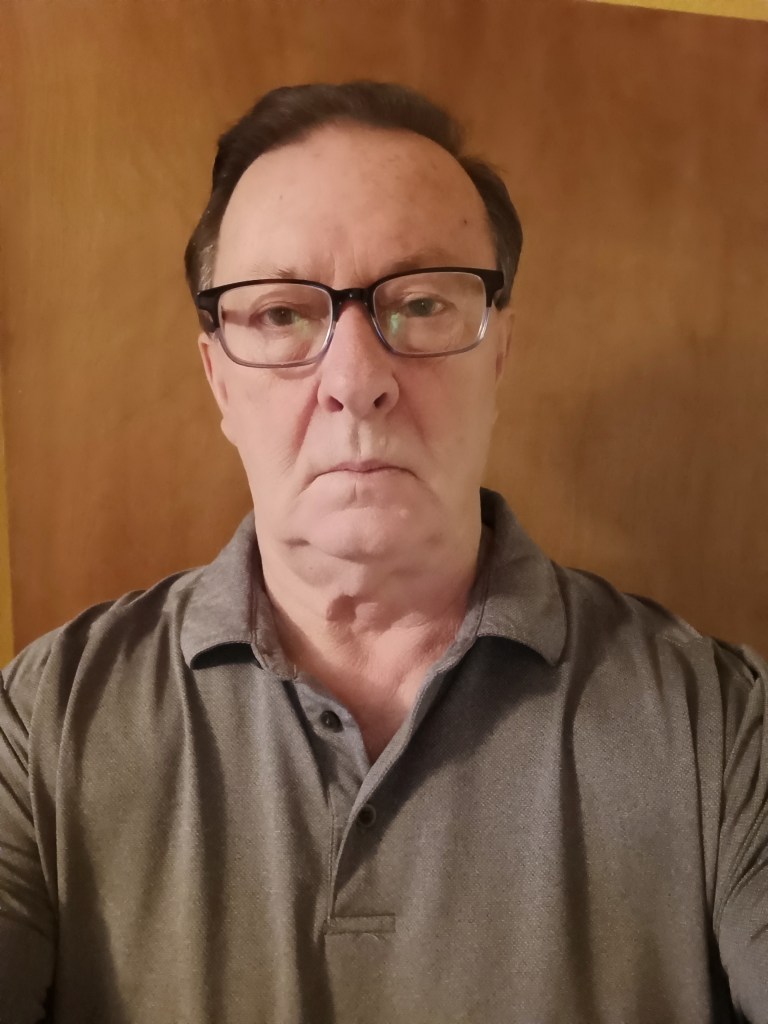

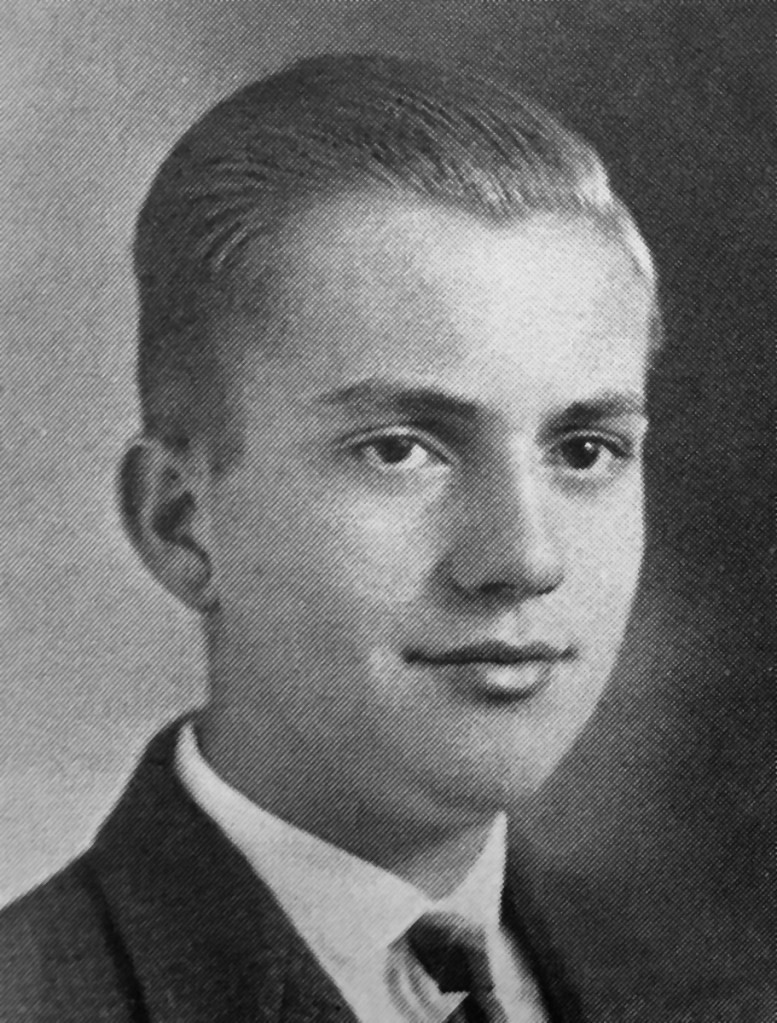

World War II veteran Matt Gutman died last Thursday, November 7, at his apartment in Allentown, Pennsylvania. He was 99. I wrote a story about his passing for my old employer, The Morning Call. For you, I’m sharing a partial transcript of my August 18, 2022, interview with him. Here, he tells about joining the Navy in 1943 and heading for the fight against Japan.

I didn’t want to be trapped in the Army or Marines.

When I was in junior high school, my brother who was in the Navy gave me one of these sea caps, and I used to wear it to school. I sort of liked the Navy because, first of all, I wanted to have good, warm chow and a bunk to sleep in, not a mud hole. … And that’s why I chose the Navy.

I enlisted at the Navy recruiting station in Allentown. … I wanted to go into the Seabees originally, [so] I talked to the chief Seabee, and he says, “What’s your occupation? What did you do?” I said, “No, I just come out of high school. I had basic electric.” He said, “Look, son, go next door. Talk to the Navy recruiter. We can’t be teaching you. We want people that are already trained.” So then I went next door to the chief of the Navy, and he enlisted me.

Then I went to Sampson, New York, for seven weeks of basic training. There was 106 of us. We trained together, marched together, ate together, everything together as a unit, and then, of course, graduated and then were given a seven-day leave to go and visit our parents, our friends. After seven days, we had to report back to Sampson for fleet assignment.

They sent me with a group of others by train down to Camp Bradford, Virginia, for amphibious training. First of all, I didn’t know what it would entail. … I knew it was land and sea. This was something new. When we got down there, they showed us all the different types of ships they used for invading an island, went over every one of them. They also told us about what to expect on those ships, and they told us these ships were made only to invade an island. That’s why they called them amphibious. They carried troops and tanks to invade an island.

That was the main purpose of the ship that I was assigned on. It was called a landing ship, tank, an LST, and they were all numbered. They never had no names. Mine was 553. I was with it all through the war. It was camouflaged brown and green. You know why? Because when we boarded that ship in Evansville, Indiana, where it was built, we seen that ship was all in tropical colors. Tropical! We knew right then and there that ship was going to be assigned to the Pacific Theater, not European, because once that ship beaches, it blends with the foliage on that island.

They taught me how to operate the Higgins boat, and I was in charge of the Higgins boat on our ship when we made the landings. I was a seaman first class then. I don’t know why I was picked, but they came and asked me if I’d like to do that, and I said, “Why not? I’m in the Navy, I’ll do what I can.” And I operated that landing craft all through my landings in the Pacific. …

After they trained me, I went to San Pedro [in Los Angeles] and Hawaii, I used that boat a lot to take people to shore, back and forth. So I was trained all along with it, you know what I mean? It only had one propeller. You had to watch the wind and currents. Well anyway, they trained me pretty well.

We only had two Higgins boats on our ship, one to starboard and one on the port side. I had the one on the port side. [As coxswain] I was in the stern. I always had to watch where I was going. These Marines and Army men we had in there, they’re all hunkered down. I had to see where I’m going, you know. I had to stand because I wanted to see where I was going, because the bow doors were up pretty high. It had a diesel engine, very noisy, and it always smelled awful. But we were young guys, we could take it. We were all young, full of piss and vinegar, and no brains.

They shipped a crew of us to Evansville, Indiana, where we picked up our ship. It was built there, right alongside the Ohio River. We boarded that ship in April 1944. The skipper took her down the Ohio River, the Mississippi River to New Orleans. That’s when the ship was commissioned. We stayed in New Orleans for four days, taking on supplies – water, fuel. Then we headed back down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico.

While in the gulf, the skipper put the ship through what is called a shakedown cruise. A shakedown cruise consists of testing all the components of that ship – the navigation equipment, all the guns were working properly, checking out the fire system we had, the fire hoses, check everything to see that that ship was ready for combat. From there we went to Panama City, Florida, where they taught us how to distinguish all types of shipboard fires we might encounter in combat. We were there about four days.

From there, we went to Gulfport, Mississippi. We were there to pick up creosote pilings. They were large logs, about 18 foot long and 2 foot wide. We wondered, what the hell is this gonna be? They loaded them on our tank deck. We went through the gulf and the Panama Canal with about seven other LST’s. And we we went up along the coast to San Diego, 108 men and eight officers. … We enjoyed liberty there. We were there maybe three or four days. We took on more supplies. We also took on a contingent of Seabees.

We left San Diego with a fleet of ships going due west. The skipper was on the P.A. system and he said, “We are now heading for Pearl Harbor.”

When we entered Pearl Harbor, we could still see a lot of the destruction that took place when they [the Japanese] bombed that harbor. We then found out that these creosote pilings, along with the Seabees, were brought there to repair the docks and ships that were destroyed in the bombings. We were there maybe about a week. We enjoyed liberty. A lot of guys got drunk, got pie-eyed. I think I had a couple of beers. We had a lot of fun. I guess the skipper wanted us to have fun.

We knew from there, God only knows where we’re gonna go.

In September 1944, Gutman landed Marines on Peleliu in his Higgins boat under fire. He went on to take troops ashore at four sites in the Philippines and at Okinawa. At war’s end, he and some others on his LST volunteered to sweep pressure mines that U.S. planes had dropped in Japanese harbors. For “the personal danger involved,” he was awarded a Navy Commendation Medal. Back home, he had active duty in the Reserve as an instructor and recruiter, retiring in 1967 as a chief petty officer.

He was more than a distinguished veteran and the subject of several stories I wrote for the newspaper over the past few years. He was my friend.