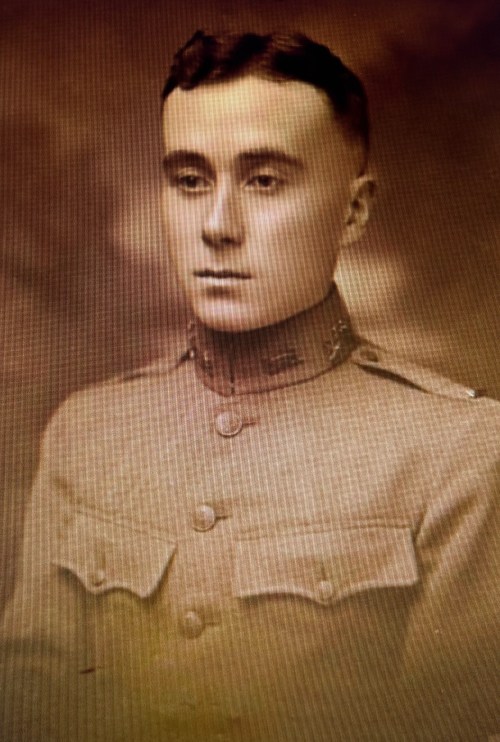

You might remember my blogs last year about an Army officer from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, who was killed in the First World War.

There’s more to tell about 2nd Lieutenant Howard Lee Strohl.

I had pieced together his story with the help of his great-niece, a unit history, the National Guard armory in Allentown, Ancestry.com, and contemporary accounts on Newspapers.com, one of which had the text of a letter he wrote home from France.

What I didn’t have was Strohl’s official military personnel file. It wasn’t at the National Archives’ National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis. “If the record were here on July 12, 1973,” said the message from an archives technician, “it would have been in the area that suffered the most damage in the fire on that date and may have been destroyed.”

But she opened another door, saying a casualty file held by the Army might have information I wanted. She suggested I write to the Army Human Resources Command’s Casualty & Memorial Affairs Operations Division at Fort Knox, Kentucky.

So in May 2023, I mailed my request with as much detail on Strohl as I could muster. Four months later, an email arrived from a tech at the National Archives at St. Louis: “We have located Howard L. Strohl’s burial case file as requested.” It turned out Human Resources Command doesn’t have World War I-era burial case files, so Fort Knox forwarded my inquiry to St. Louis.

I got directions on how to pay electronically using the U.S. Treasury’s Pay.gov service and did it right away. The cost was $28.80. “Please allow time for the scanning and uploading process to be completed,” the archives tech said. “Our staff is minimal and all requested records need to be digitized and redacted prior to delivery, so we are looking at a much longer turnaround than is typical.”

Six months passed. I gave the tech a nudge in an email. She wrote back promptly that I’d be getting the record in the next several days. Sure enough, an email arrived with a link to a PDF scan of the file.

Of its thirty-eight pages on the disposition of Strohl’s remains, the last one interested me the most. It’s an account of his final moments, given after the war by a sergeant who had been with him.

(National Archives at St. Louis)

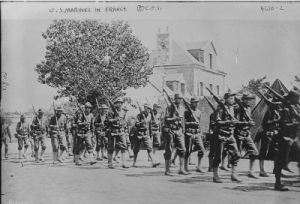

Strohl and Sergeant Claflin L. Bowman were in Company D, 109th Machine Gun Battalion, part of the 28th Infantry Division. In early August 1918, they were among the doughboys battling German troops along the Vesle River at Fismes, a village in the Champagne-Ardenne region of northeastern France.

“The carnage was awful,” a unit historian would write, “and it was our 28th Division which successfully withstood the attack, at a fearful loss.”

Bowman said Strohl fell about 2:30 p.m. August 9 – a day after the 109th got into the fight. He told an officer asking about the circumstances of Strohl’s death:

Just before the Lieut. was hit I was with him in the cellar of a house which was on the street leading from the city hall to the Vesle River. Lieut. Strohl left the building for the purpose of securing information but was hit by the fragments of a shell just as he reached the street. He was wounded in the chest and in the thigh. Lieut. Strohl[’s] wounds were dressed at once but he died without regaining consciousness. He is buried in the yard at the hospital at Fismes.

Six days earlier, Strohl had written to an aunt and uncle in Allentown about seeing “all the grim horrors of warfare.” If he hadn’t been killed, he would have received an order the next day to return to the States for further training.

He was twenty-three. Back home in the Lehigh Valley, he left a wife, who had given birth to their son after he departed for France.

His remains were removed from the hospital yard and reburied two weeks before the Armistice in American Battle Area Cemetery 617 at Fismes. It was Grave 67, Row C, marked with a cross.

Sergeant Bowman, of Myerstown, Pennsylvania, was interviewed in February 1919. The officer who took his statement, 2nd Lieutenant Charles C. Curtis, went on to become a major general in the National Guard and command its 28th Infantry Division. Allentown’s National Guard armory, home of the 213th Regional Support Group, bears his name.

—

(National Archives at St. Louis)

Strohl’s burial case file shows the military’s care in dealing with his family and bringing his remains home. It’s clear the war dead of more than a hundred years ago were honored and their kin treated with respect just as they are today.

Both Strohl’s widow, Ada, and father, William, asked the Army for information about his remains. William Strohl wrote to the Adjutant General’s Office in Washington in April 1919:

Having been informed that the Government intends to remove and send home the bodies of the American soldiers, and being deeply interested in this move on account of having lost my son, Lieut. Howard L. Strohl, 109th Machine Gun Bat. on last Aug. 9th, I will kindly ask you to forward me any information you may have concerning such action.

The office responded with the War Department’s policy and said, “In due time, you will be asked for information relative to your wishes in the matter of the disposition of the remains of your son.”

According to the policy, the nearest next of kin – in this case, Ada – could choose to have the body returned to any address in the United States, interred in the National Cemetery at Arlington, Virginia, or any other national cemetery, or left in Europe. The government would pay the full cost for the transfer of bodies.

Ada asked that her husband’s remains be brought to her in Hellertown. But she remarried in 1920 before that could happen, and as a result no longer qualified as his nearest next of kin. That was now her toddler son, Howard R., with Bethlehem National Bank as his guardian. The bank wanted Strohl’s body delivered to his father in Bethlehem.

In April 1921, the Graves Registration Service of the American Expeditionary Forces removed Lieutenant Strohl’s remains from the American cemetery at Fismes. They were placed in a casket and delivered by rail to the port at Antwerp, Belgium.

(National Archives at St. Louis)

The Army ship Wheaton, built by Bethlehem Steel, carried Strohl across the Atlantic. On June 11, the transport docked at Pier 42 in Hoboken, New Jersey. From there, the Lehigh Valley Railroad took him home to Bethlehem. He was laid to rest, finally, in Towamensing Cemetery.