Walter Warda was drafted into the German army in April 1943, when he was 17. Eight months later, he was captured by the Red Army on the Eastern Front. Ahead of him were years of suffering in deathly Soviet prison camps.

I found out about Walter from my mother-in-law, who knew him because they lived in the same apartment building for seniors in Allentown, Pennsylvania. When I interviewed him 10 years ago for The Morning Call, he told me his amazing story of survival. You can read it here.

—

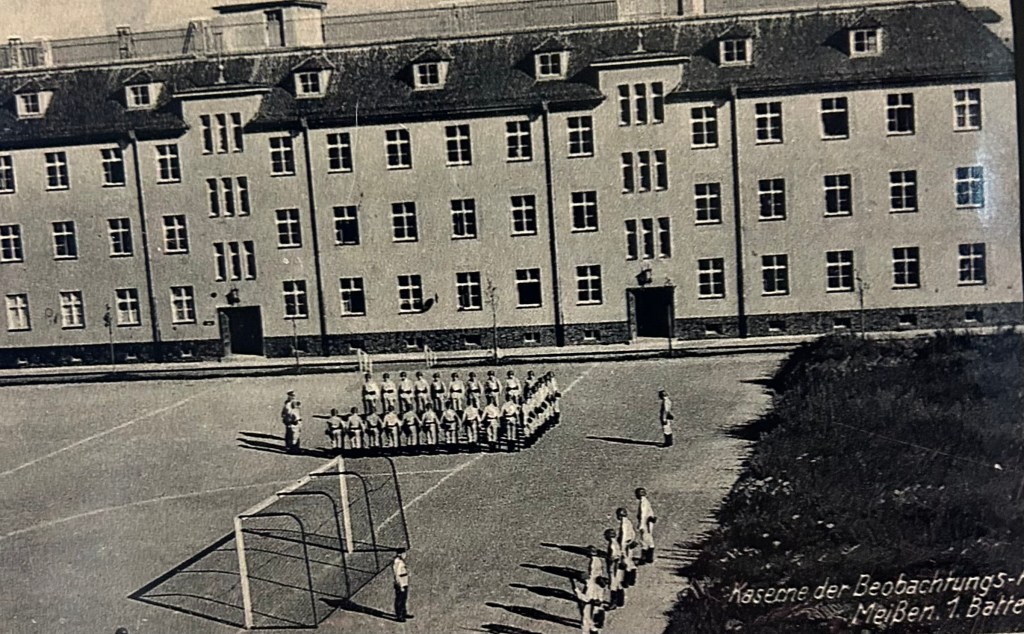

Walter was born in Duisburg-Hamborn, near the Dutch border, to a Thyssen steel plant foreman who’d lost an eye fighting for the Kaiser. In the Wehrmacht, Walter was trained as a radio and telegraph operator in an artillery observation battalion, a Beobachtungs-Abteilung, and sent by train to the war in the east.

“There was not one soldier who wanted to go there,” he said. “That was like punishment.”

They got as far as southern Ukraine, near the Black Sea, where the Red Army forced them back into Axis-allied Romania and Walter was captured. But he escaped from a line of prisoners on the march, evading shots fired by Russian guards in pursuit.

He and a buddy fled into Bulgaria and reached neutral Turkey on foot. But they were captured in a border town by Russians on horseback and marched to Romania’s Black Sea port of Constanta. Held there for a while, they were forced to unload ships carrying American planes for the Soviet military.

A train took them through the rubble of Stalingrad and up the Volga River to a camp near the Russian town of Zelenodolsk. In horrendous conditions with hardly any food, Walter, who stood just 5 feet tall, went from 145 pounds to 68 while beset with typhoid fever. He was hospitalized for seven months.

Sent to a smaller POW camp, he escaped and slyly hopped a freight train in hopes of reaching safety in Finland. But after he got off the train to get on another, a boy saw him hiding and called police, and he was captured short of his goal. He had been on the lam for 20 days.

Walter was taken to a camp in Kuibyshev on the Volga, where he was viciously beaten, then to another camp where he was kicked so hard, he flew against a wall. His time there was filled with hard labor.

In yet another of nearly two dozen camps where he barely survived, he met a doctor who was a fellow prisoner from near his hometown. Freed and sent home, the doctor informed Walter’s parents in 1949 that he was alive.

“My mom cried over that,” he said.

One day in 1950, five years after the Nazi defeat and the end of World War II, the Russians freed him and almost everyone else in the camp.

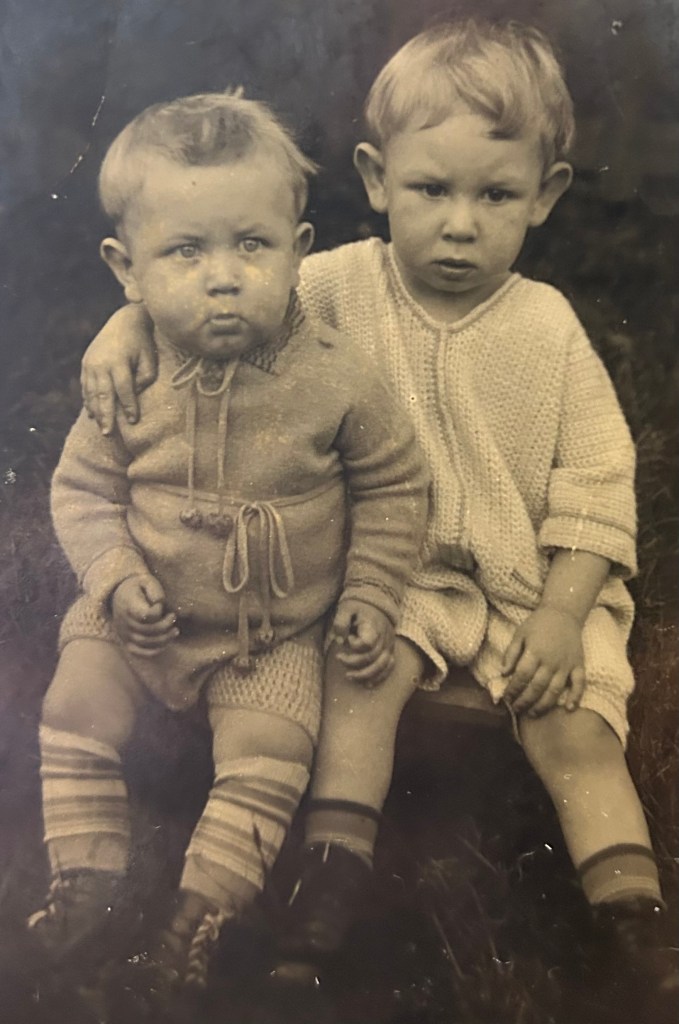

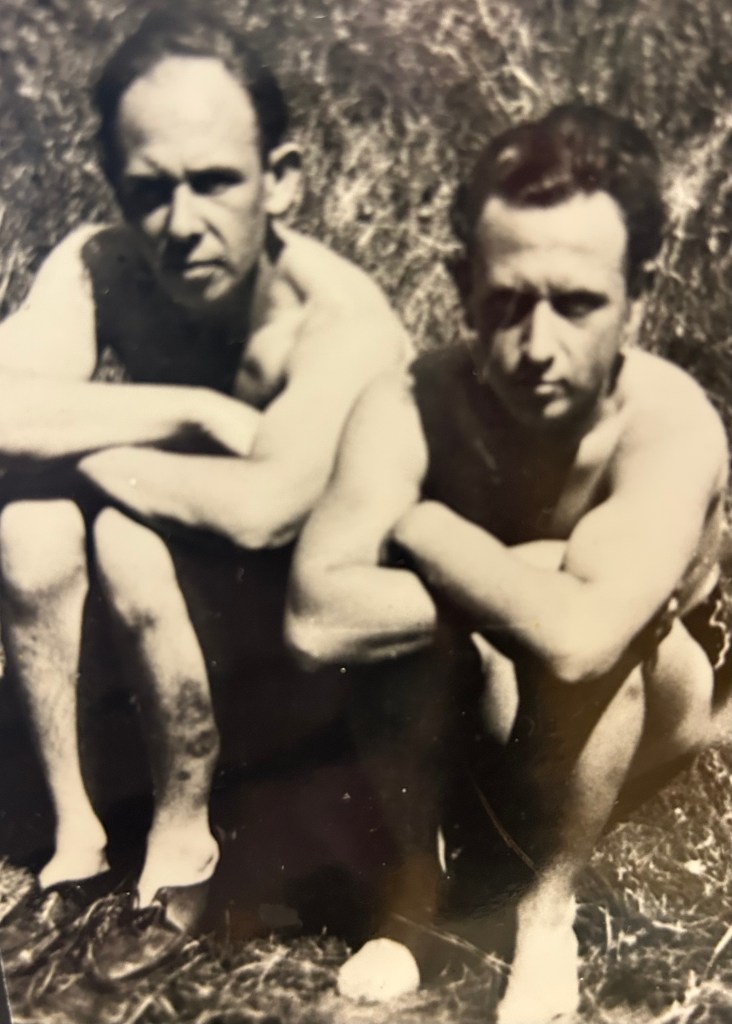

Walter returned to Duisburg-Hamborn and found his brother, Wilhelm, playing the accordion in the kitchen. A Wehrmacht soldier, “Willi” had been badly wounded near Leningrad and, like Walter, spent several years as a POW of the Russians.

Walter married a seamstress, Irma Plas, and toiled at a shipyard. With a son in tow, they came to America in 1954 and settled in Allentown, where Walter had two uncles. A daughter was born there.

For 33 years, Walter welded and did maintenance work at Mack Trucks. He was a happy joke-teller, gifted woodcarver and devoted gardener. He and Irma belonged to a German-American singing society, the Lehigh Saengerbund, for more than six decades. Irma died in 2019 at the age of 91.

Walter believed he survived the Eastern Front and his years of appalling captivity because God was with him.

“He protected me in every situation. I had a feeling He was helping me all the time.”

—

I stayed in touch with Walter over the years. He made folksy woodcarvings for my wife and me. He served German beer when I visited and seemed to enjoy our talks. Last August, invited by his daughter, Christa, I attended a party marking his 100th birthday, an extraordinary milestone, given the horrors he endured on the Eastern Front and as a POW of brutal Soviets.

Walter died in January. Here is his obituary. We said goodbye to him at a church service this past weekend. He was a kind and gentle man. He was my friend.

Ruhe sanft, Walter.

Thanks, David for sharing this story and giving another perspective of the those who experienced these horrendous times. It reminds me of a friend in the Vietnam War who had previously been a border guard in the Soviet Union and defected to the West, came to the US, got drafted and ended up fighting the war. We talked often of his experiences under communism and his defection and how he viewed his experiences.

LikeLike

Amazing, Fred, that your friend went from Soviet border guard to Vietnam. Seems like going from bad to worse. I hope he got home OK.

The other night I watched a documentary on Netflix about reporter Seymour Hersh and how he broke the My Lai story. He was dogged and fearless! When I went to Vietnam in 1998 to follow my cousin Nicky’s footsteps, I visited the massacre site. It was overwhelmingly sad. A young Vietnamese woman who was a guide there told me: “We are not angry at all Americans, only the ones who did this.”

LikeLike

i am so glad she understood that it was the individuals and not the guilt of all. too witnessed the same kind of atrocity with Delta Company 3/21-196 Bn. with a single solder killing perhaps 10-12 women and children. He was killed about 6 weeks later in a firefight,. One of the other soldiers who also witnessed it later told me that this soldier “got his punishment.”

LikeLike

Enjoyed your incredib

LikeLike

Hi Jack, thanks for writing. Somehow all I got was “Enjoyed your incredib” and then your message got cut off.

LikeLike

Your friend Walter’s resilience is astounding! As is the fact that he remained a kind and gentle man in spite of all his terrible experiences during that war.

Thanks for telling his story.

Jan

LikeLike

Thanks, Jan, ever faithful reader. Walter was indeed a gentle soul.

LikeLike