(Bill Wolfe)

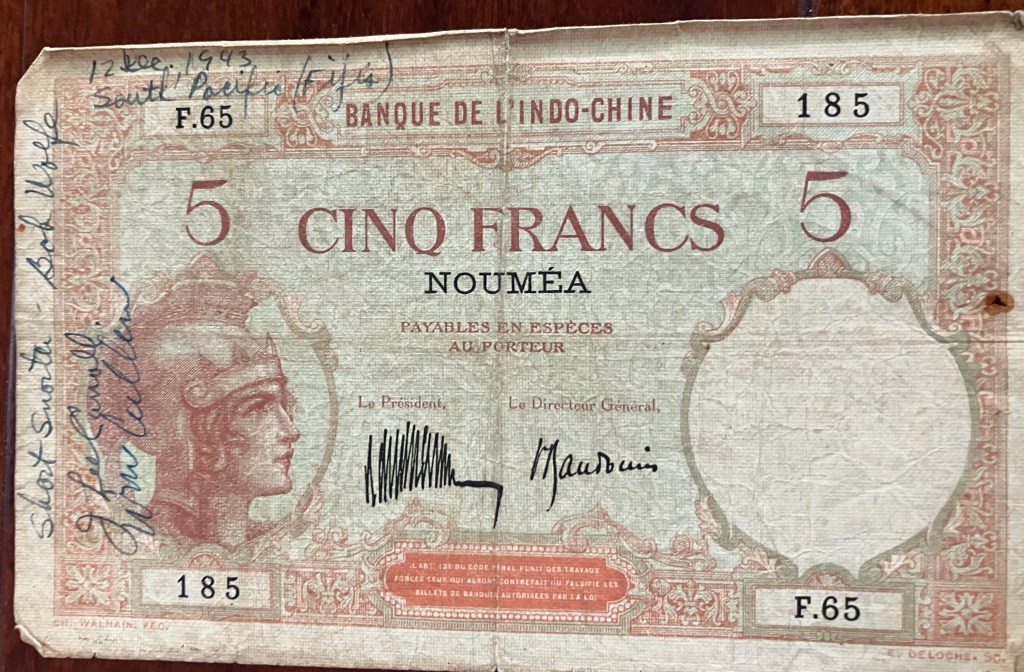

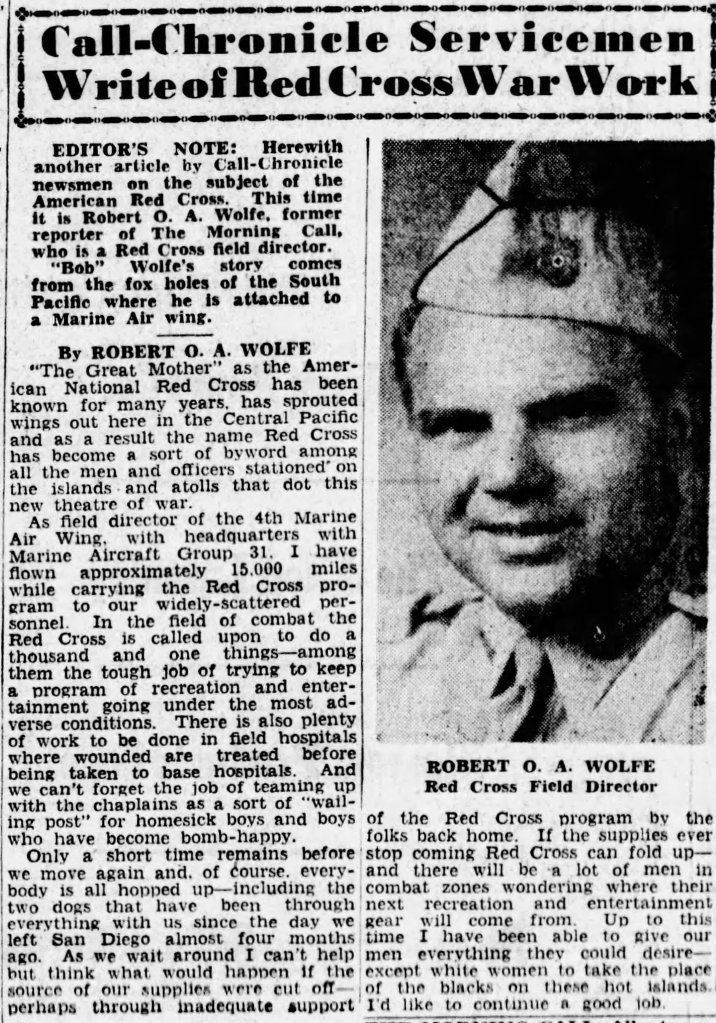

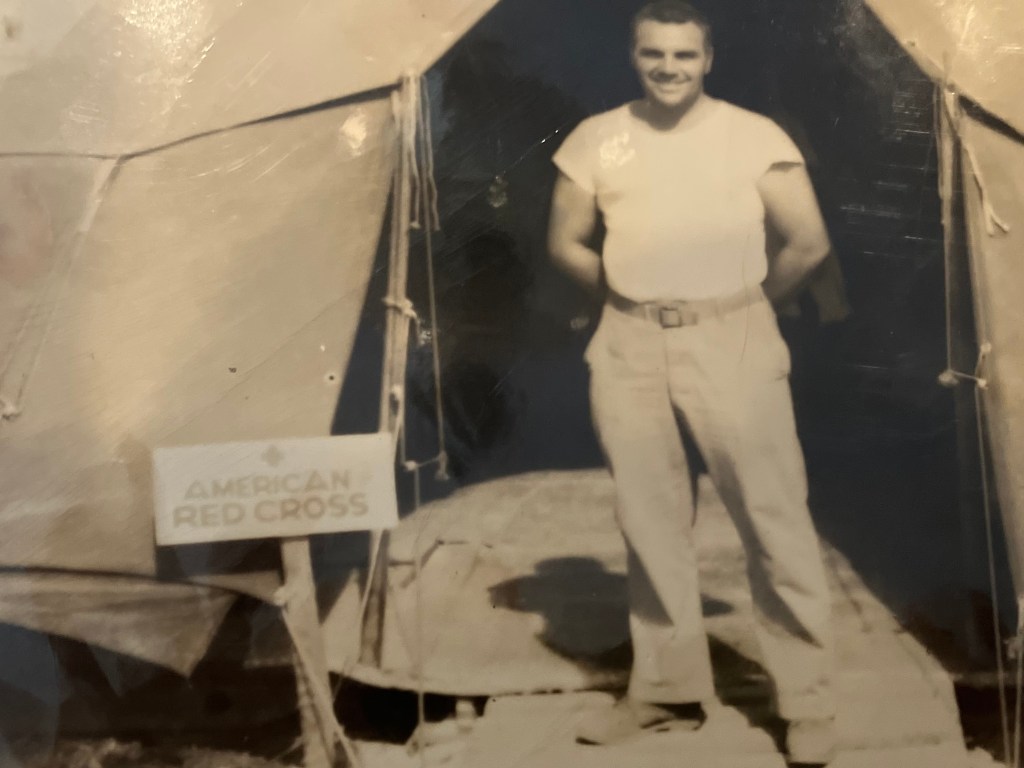

Newspaper reporter Bob Wolfe was an American Red Cross field director with the Marines in the Pacific during World War II. Among his chores, he provided softball and volleyball gear, set up boxing bouts and entertained island natives with boogie-woogie records. A shrapnel wound earned him a Purple Heart, for which he was eligible because he worked for the military.

An athlete, he had started at The Morning Call of Allentown as a sportswriter in 1929 while still in school. According to a chatty column in the paper that December, he “has his arm out of the sling again after having broken it recently for the seventh time.” At Allentown High School, which he graduated from in 1930, he was a football lineman and standout swimmer.

His work with the Red Cross dated to 1931, when he passed the nonprofit’s first-aid course and became a member of its Life Saving Corps. A head injury he suffered while swimming at a local park that year dogged him for many months. He was admitted twice to the University of Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia. On top of that, a lightning strike shocked him while he was walking home from a ballgame, landing him in an Allentown hospital for about a week.

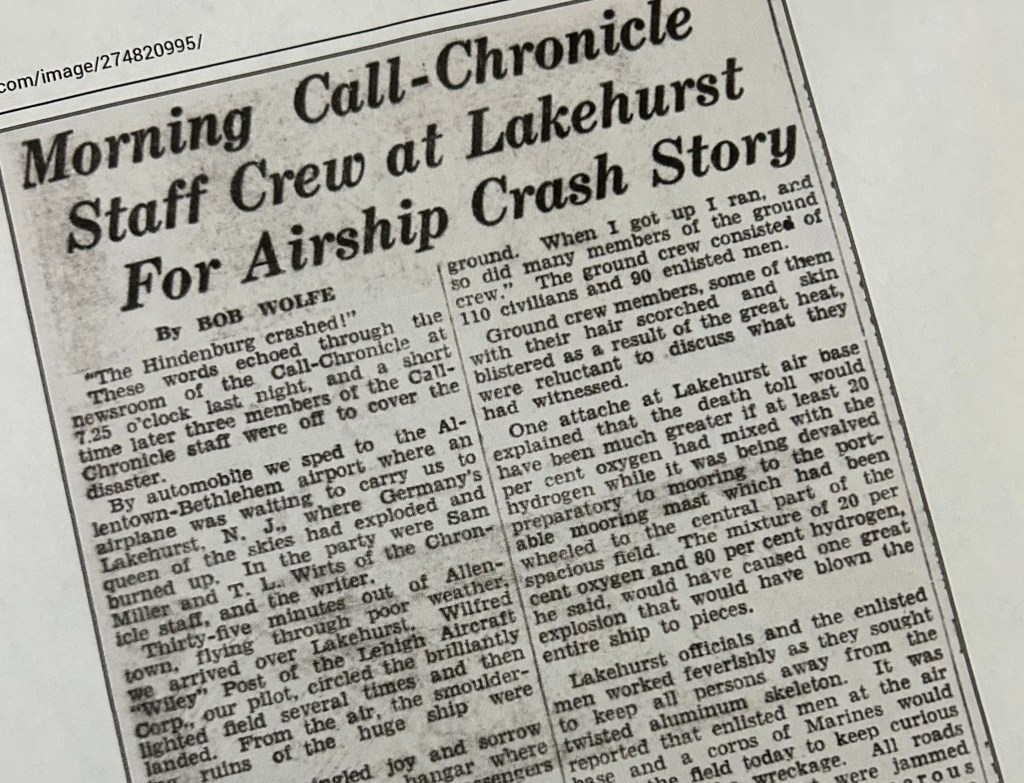

As a newshound, he sped to Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1937 to cover the Hindenburg disaster. “Scenes of mingled joy and sorrow were common in the hangar where relatives of some of the passengers and persons who were to have embarked on the return trip at 10 o’clock last night were gathered,” he wrote on May 7. “Pieces of ribboned fabric, which floated to the ground after the two explosions in the air, were guarded closely by enlisted men at the hangar.”

Thirty years old, married and the father of a 3-year-old boy, Wolfe took Red Cross training in Washington, D.C., in 1942. When he came home from overseas two years later, he wrote a report for the service organization that describes an aspect of the war unfamiliar to many of us. Here is his entire report, which took up 14 typewritten pages:

—

STATEMENT BY

Robert O.A. Wolfe

American Red Cross Field Director

of Allentown, Pennsylvania

on his return from the MARSHALL ISLANDS,

where he served with the United States Marines

The American Red Cross

Washington, D.C.

Wednesday, July 12, 1944

I was with Marine Aircraft Group 31, originally attached to the 3rd Marine Air Wing at Cherry Point, North Carolina.

(Bill Wolfe)

When the group arrived in the South Pacific, it was detached from the 3rd Air Wing and became a part of the 4th. Just before we left Wallis Island, which is about 300 miles south of Funafuti, Colonel C.R. Freeman, group commander, called in the Red Cross man — myself — and wanted to know how much money was available for the purpose of creating a unit PX [post exchange]. I explained that so much money was in my revolving fund, and he asked if it were possible to advance sufficient cash finances for the purchase of supplies, including 100 crates of cigarettes. This money was advanced to him on the signature of his PX officer, Captain George Cruze, a Californian.

While we were preparing to embark from Wallis to go into the Marshalls, the supplies were picked up at Funafuti, put aboard one of the transports which was to take us into the new campaign as a small part of a huge fleet. That was the Marshall Campaign.

Colonel Freeman approached me on approximately the 15th of January. Prior to embarking at Wallis, I purchased and made ready for distribution aboard the transports two crates of playing cards, each crate containing 427 decks. The voyage from Wallis to Makin Island in the Gilberts, where we were to rendezvous with the fleet, was uneventful except for a tropical storm which tossed the ships around like corks in an open sea. The playing cards mentioned before were put to use practically 24 hours a day, with some of the Marines playing games around the clock. They’d sit down at 10 in the morning, and they’d still be playing at 10 the next morning.

When we left Makin to go into the vaunted Japanese waters of the Marshall Islands, we had strong seapower escorting us, as well as air coverage. It was a sight that millions would pay fabulous fees to see when we sailed into the waters of Roi-Namur at the northern tip of Kwajalein Atoll, where hundreds of ships were lying off shore awaiting their part in the big battle. There were more carriers than you could count on your hands, battleships were numerous, there were plenty of destroyers and, in fact, every type of warship which goes to make up our powerful Task Force 58.

The Marines went ashore on Roi on the 1st of February after the atoll had been plastered by sea and air power, and in four days’ time both Roi and Namur were secured, with the exception of the few snipers who holed up in the drainage system which skirted the runways and revetments on Roi. The drainage systems were concrete, about 18 inches wide, about 14 inches deep, and had openings about 2 inches wide with concrete slabs thrown across the top. In these drains, Japanese snipers would stick a rifle through one of the openings and take potshots at Marines or Seabees who were working on the runways. The last of these snipers were killed about a week after the battle itself ended.

On the island of Roi, a fire which started during a bombing early in the morning on February 12th destroyed vast quantities of supplies and gear, but fortunately most of my recreation supplies arrived a few days later in fairly good shape. These supplies comprised practically the only recreation gear on both islands and were put to good use and brought a great deal of pleasure to Marines and Navy personnel during their off hours.

Among the supplies were softball gear, volleyballs and nets, footballs, diving glasses, a large quantity of small games, including acey-deucey, dominoes, checkers, chess, bingo and dartboards. Also among the supplies were 800 songbooks, which included both popular and old-time songs which the men sang with much gusto during the evening hours when there was little else to do. They were the official Army-Navy songbooks.

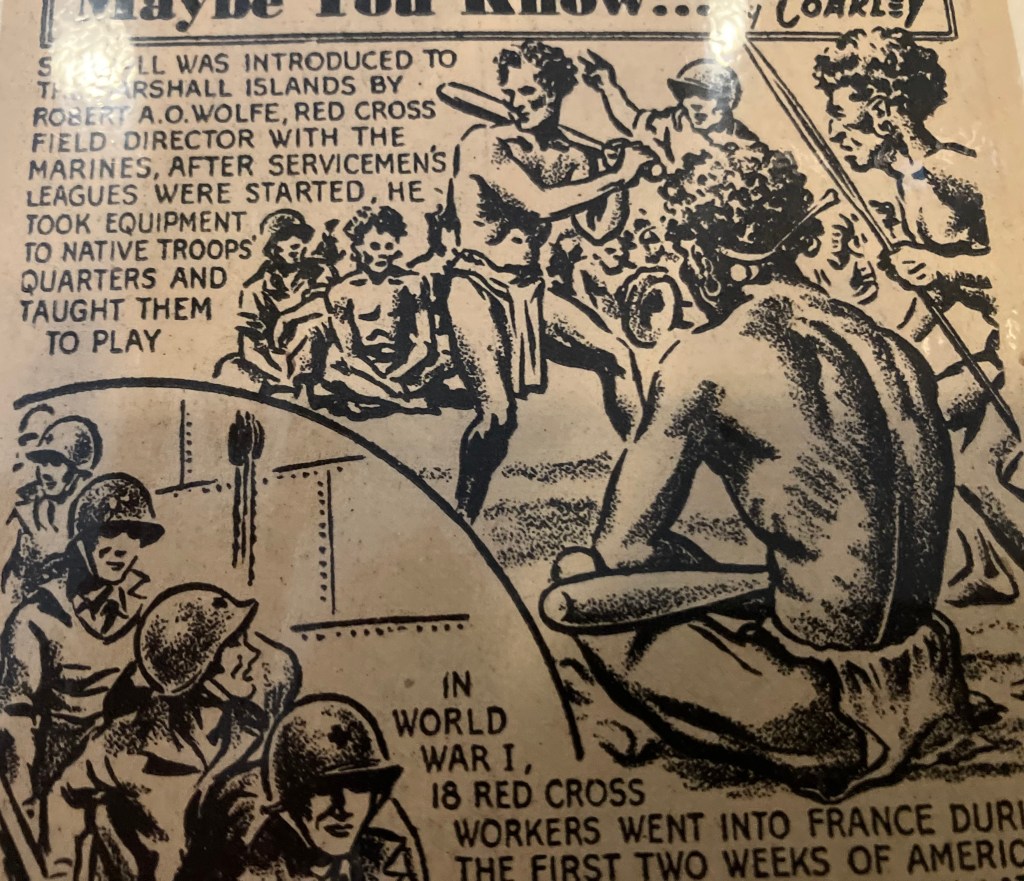

With the softball gear available, a number of leagues were soon organized, and there probably were more softball games played on Roi landing strips in one week than in a medium-sized city in an entire summer. Softball was played as early as the 14th of February, which was exactly two weeks after the initial landings on Roi. That can be considered as remarkable and another sign of the ingenuity of American fighting men when it is taken into consideration that the islands were nothing more than a pile of rubble after the battles were ended.

The softball leagues were organized principally by Lieutenant (j.g.) John R. Burrington, USNR [Navy Reserve], and an alumnus of North Dakota University with the class of 1938 and recreation officer for ACORN 21, and myself. Lieutenant Burrington handled all the volleyball.

The first boxing in the Marshalls was a result of a challenge issued to Captain Eben Hardy, USMCR [Marine Corps Reserve], of New Orleans, an alumnus of Tulane, and myself, by the athletic and recreation officer of the USS Curtis, which was lying at anchor in the lagoon at Kwajalein Island on the lower end of Kwajalein Atoll. The USS Curtis is a seaplane tender and served as the flagship of Admiral Hoover, the military governor of the Marshall Islands.

With the challenge at hand, I approached Lieutenant Burrington on the idea of running a Roi-Namur Golden Glove Boxing Tournament to select a team to oppose the Curtis boxers. The idea was put into a memorandum and sent to Captain E.C. Ewen, USN, island commander and a former football player at the Naval Academy at Annapolis. Captain Ewen gave his hearty approval to the idea and was a driving influence in the successful tournament which quickly got underway. The brunt of the work in arranging for the tournament was carried by Lieutenant Hugh Gallernau of Chicago, former Stanford football great and a member of the Chicago Bears for two seasons prior to his enlistment in the Marines, and Lieutenant Burrington and myself. Commander Chapline, an old-timer in aviation and commander of the ACORN 21 unit, also gave great support to the movement and was in a ringside seat the night of the semifinals, when it was announced that he would be relieved of his command and sent to another station to take a new command.

The first-round bouts were conducted on a sand spit being filled in between the islands of Roi and Namur, and the only discomfort suffered by the spectators was the occasional rustle at their feet by the large rats which make the island their home. The rats are almost as big as cats.

The semifinal bouts and the final bouts were staged on a ring set up at the end of a runway on Roi, and although a heavy rain broke during the semifinals, no[t] one of the men left their seats, and the bouts continued as though a brilliant moon were shining. The boxing gloves used in the tournament were “bummed” from the Army at Kwajalein Island. Kwajalein Island was spared of air raids and their supplies were large in comparison with our meager quantity.

(Bill Wolfe)

Kwajalein Island is just 45 miles south of Roi and forms the extreme northern tip of the atoll.

The gloves were brought into Roi by one of the Navy attack planes which made the return run in about half an hour. When you consider they have to take off, put down on the deck, pick up the gloves and be off again, you will see that half an hour is not much time to make the run.

Lieutenant Robert McAllister, USMCR, of Los Angeles flew me to Kwajalein in an SBD, a Dauntless dive bomber, to pick up the gloves. Four sets of gloves were used up in the tournament, and in the training program which preceded the bouts, approximately a dozen sets of used gloves were used, which had been secured from ships at anchor off Roi and also from the salvaged supplies after the bombing of Roi itself.

The boxing at Roi-Namur was the first in the Marshalls, and in view of the fact that the Japanese engage in jujitsu and judo instead of the American sport of boxing, it is believed that the Roi-Namur tournament was the first boxing in the Marshalls in many years.

Softball was introduced to the Marshallese natives by the Red Cross when I took to their small island just south of Namur two softballs, one bat, two pick handles and a dozen asbestos hand gloves. The natives knew nothing at all of softball or baseball, but they readily grasped the idea of the game when I spent an afternoon with them on an expansive beach at their island. The natives were quartered on Anton Island, which was less than 100 yards square.

In addition to the softball gear, I gave them a volleyball and a net, an old phonograph which had been beaten up in the bombing but was repaired by some Seabees, and some boogie-woogie records. The records were played for the first time one moonlit evening on the beach, where all of the natives gathered at the command of their leader. The women wore Mother Hubbards, and the men were attired in whatever clothing they were able to gather or beg from the servicemen. Some of the men wore shirts, while others were stripped to the waist.

The boogie-woogie records gave the natives a great laugh, and it was amusing to our small group of whites that after each record was played, they would all shout “OK” and they would clap vigorously.

In return for the phonograph music, the natives sang some of their native songs in beautiful harmony and rhythm. I often wished that I had a recording machine to record their music.

The Marshallese natives are very religious and are 100% Christians, principally Baptists. They had a native Baptist preacher there. He was a man about 70 years of age.

The only Marshallese native I came in contact with who was able to speak fluent English was a young man who had been educated at a college on the West Coast of the United States. His name is Laamanelli, and he is the leader of the group.

The natives, during the bombardment which preceded the battle, had worked their way from Roi and Namur, where the heavy shellings were concentrated, to small islands down the atoll. Eventually, the natives were rounded up by Lieutenant Collyer, USNR, civil affairs representative at Roi. The natives, deprived of their source of food when the shellings and bombings destroyed most of the coconut trees as well as the rice which had been stored on the islands, had to be subsisted by the Navy. The male members of the family would work on the various islands, helping to clear the debris and also to move supplies, and in this manner worked off their board.

The Marshallese are a healthy-looking type of people. They are of medium build, and the women have long, coarse, black hair. They all go barefooted. The men keep their hair fairly close-cropped, and when working in the sun, they always keep their heads covered with a turban-like cloth.

Lieutenant Collyer made the native women very happy one day when he distributed among them necklaces, bracelets, rings, hair ornaments and earrings. Although purchased at a five-and-10 in the States before leaving this country, they might just as well have been priceless jewels, as far as the natives were concerned. I doubt whether I have ever seen a happier group of people than those women were the day Lieutenant Collyer distributed these things. Lieutenant Collyer, after calling the women together, explained that the jewelry was a token of thanks for what the male members of the families had done so far, and also for the laundry which the women were doing for some of the officers. By the way, they launder by pounding the clothing against a piece of coral rock in brackish water.

There were only about a dozen service people who actually mingled with the natives. Parties of native men were transported each morning by landing craft from their island to Roi or Namur for the purpose of doing cleanup work and also helping transport supplies around the islands.

Laamanelli, the leader, explained in Marshallese language that the American Red Cross was a neutral agency operating with troops in battle, and he told the natives that their recreation supplies and the phonograph and records were a gift from the Red Cross field director who landed with the Marines on Roi. This little speech by Laamanelli brought a cheer and great hand-clapping.

Laamanelli knew a little about the Red Cross but was surprised to know that the American Red Cross was sending men with the troops into the battle zones. He said that the Japanese, as long as they were in the Marshalls, never had Red Cross representatives with them.

The phonograph was set up on a gasoline drum on the white, sandy beach which fronted on the lagoon. The natives squatted in a semicircle around the phonograph, and to their backs were a few small lean-to’s which provided their shelter and also some coconut and pandanus trees. There was also some undergrowth which gave the island a typical tropical setting.

The phonograph was first played as the natives faced the setting sun. The sun set over the stacks of some of the powerful warships which were at anchor in the lagoon, and as it slipped farther beyond the horizon, it left a brilliant red glare in the sky, which Laamanelli said indicated another hot day for the morrow. The tide was receding at the time, and as the waves rolled down the sloping beach, there was a rhythmic pounding of the surf.

To the northwest, the ocean side of the island was being pounded by high breakers which rolled over the coral reef which circles the entire atoll. The natives were quiet as the phonograph beat out the boogie-woogie, with the exception of occasional laughing by some of the younger folks and the women. The men were as sober as church deacons, and it was only after the record had played through that the men would holler “OK” and then clap and shout.

Laamanelli is a much larger man than the average Marshallese and stands about 5 feet 11 inches. He is a well-built man of about 40 years of age, and his leadership among the natives in his section was passed on to him by his father. Laamanelli is a keen-thinking man and has his natives always under control and at the tips of his fingers. He knows everything that is going on and knows where everybody is.

There are only 8,000 Marshallese in all the Marshalls. Laamanelli is the leader of the natives around Roi and Namur, and they might total only 300.

The Marshallese natives are recognized as among the best navigators in the world, and before the Americans landed, they did considerable fishing both in the ocean and in the lagoon, principally for the ulua, barracuda, and a type of tuna which abound in the waters around Roi and Namur.

Laamanelli wore a pair of GI trousers and a white shirt, apparently given to him by some Navy man. He was barefooted and at times wore shell-rimmed glasses.

(Newspapers.com)

The Japanese provided rice and tinned fish to augment their supplies of fresh fish, coconuts and pandanus.

The natives were on Anton Island temporarily, having been driven from their natural habitats by the invasion, and no doubt by now they have been installed in more permanent living quarters. Their quarters were built out of odds and ends of wood, and the temporary lean-to’s on Anton were constructed out of K-ration boxes with palm fronds woven to form a waterproof roof. The way they do that is really quite ingenious.

Following the phonograph concert, Laamanelli extended his personal thanks to both Lieutenant Collyer and myself, and he expressed the hope that we would return soon with more music. The second trip we made back to the island, we took some Benny Goodman, Bing Crosby and other popular music along, as well as the “Marines’ Hymn,” “Anchors Aweigh,” and the national anthem. The phonograph was left to the natives for their entertainment.

It should be explained that the phonograph had been severely damaged in a bombing and was considered a total loss until one of the energetic and ingenious Seabees went to work on it and put it in operation again.

The needle shortage became serious at one time, but the natives sharpened their supply of needles with coral stone and seemed to encounter no difficulty in keeping the machine in operation.

Lieutenant Collyer, a small garrison of Marines and myself were present that night, and following the concert we opened up some fruit juices and some boxes of K-rations and had a little party among ourselves. The natives seemed to enjoy their little bill-of-fare, which consisted of tinned fish and coffee which they prepared themselves with the brackish water. They had American coffee. Approximately 150 natives were present at the concert; all but a few were there. The old folks were in their beds. There were no babies there; the youngest child was about 4 years old.

Laamanelli pointed to the Red Cross insignia on my collar during his little talk to the natives, in which he explained the Red Cross and the work it was doing there.

Incidentally, the concert took place three weeks after the landing.

—

Back home, Robert Owen Andrew Wolfe lectured about his Red Cross experience in the Pacific. He was secretary of the Allentown Chamber of Commerce, worked for Western Electric in public relations and in 1962 edited Allentown’s bicentennial commemorative book. He was president of Wiley House, which helped children with emotional problems, and served on the Allentown YMCA board and as president of the Catasauqua School Board.

(Bill Wolfe)

He and his wife, Elsie, had two sons and a daughter and lived in North Catasauqua. He died in 2004 at age 91.

Fifteen years ago, his younger son Bill sent the 1944 Red Cross report to me at The Morning Call with a note, “I hope you find it as interesting as our family does.” I spoke with Bill, read the paper and tucked it into a file of prospective stories. It stayed there. When I retired, I brought the file home.

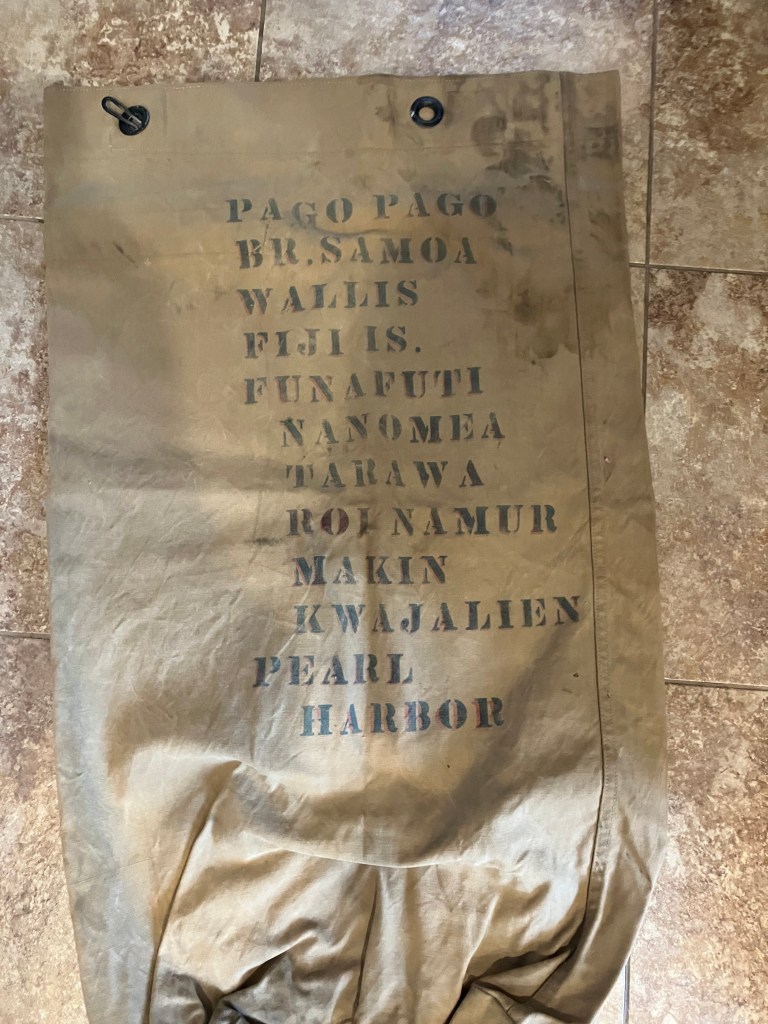

A few weeks ago, I came across the report and called Bill about posting it on my blog. He sent me images from an album his mom kept, along with photos of some keepsakes, and mentioned something I hadn’t read anywhere — that his dad was treated at Walter Reed General Hospital for elephantiasis he had contracted overseas.

“In the field of combat,” Bob Wolfe wrote for The Morning Call in 1944, “the Red Cross is called upon to do a thousand-and-one-things — among them the tough job of trying to keep a program of recreation and entertainment going under the most adverse conditions. There is also plenty of work to be done in field hospitals, where wounded are treated before being taken to base hospitals.

“And we can’t forget the job of teaming up with the chaplains as a sort of ‘wailing post’ for homesick boys and boys who have become bomb-happy.”

Another great war story! I had no idea that the red cross teamed up with marines and played such a key role in public relations with islanders as well as keeping the navy personnel entertained. I also want to thank you for defining PX! I never knew what the letters stood for…so maybe they sent and recieved mail through the PX as well as purchasing goods from ‘home’. That would make sense as the US Army, AID, Embassy etc folks…could send letters through the quicker US system but we civilians had to use the local postal system that took at least two weeks to arrive at its destination!! When I was a kid in Ethiopia, we used to go to the ‘PX’ for ‘american’ goods until US civilians were no longer permitted…can’t recall why we were no longer allowed.. Not so fun fact: also in Ethiopia, it was common to see people with elephantiasis….it really imprints on a kid’s brain. Anyway, I love learning some history through people’s stories. Thanks!

LikeLike

Ohmygosh, Jan! Sometime when you have eight hours or so, I’d love to hear your story of growing up in Ethiopia. … Guess what? Until I read Bob Wolfe’s report, I didn’t know the Red Cross teamed up with the Marines either. Amazing! Remember back in the War on Terror, they used the term “embedded,” as in: Reporters were embedded with military units.

LikeLike