On this 83rd anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, I’d like you to meet the Pearl Harbor survivors I’ve known and written about. All 13 of these servicemen lived in Pennsylvania, and all, sorry to say, are gone. Here’s my salute to them:

—

Navy electrician Jim Murdy was aboard the light cruiser Helena on December 7, 1941. The Helena was tied up alongside the minelayer Oglala in Pearl Harbor’s repair dock. Just before 8 a.m., an aerial torpedo passed underneath the Oglala and hit the Helena’s forward engine room. General quarters sounded, and Murdy hurried to his repair-party station. “What happened?” he asked an officer running past. “You damn fool, we’re being bombed by the Japanese!” “We are?” Murdy asked. “What the hell did we do to them?” After the attack, the captain addressed his crew. Here’s how Murdy remembered it: “The Helena‘s old man took the horn and announced, ‘Gentlemen, we had a rough time today. We had 35 men killed, and there’s 105 men put in the hospital, and there’s a number of those who are not going to survive. This is probably going to be a long war. And the one thing I will tell you is: Make your every move count. We will win! But make your every move count!'”

From my interview with Murdy in the December 7, 1999, Morning Call of Allentown, Pennsylvania

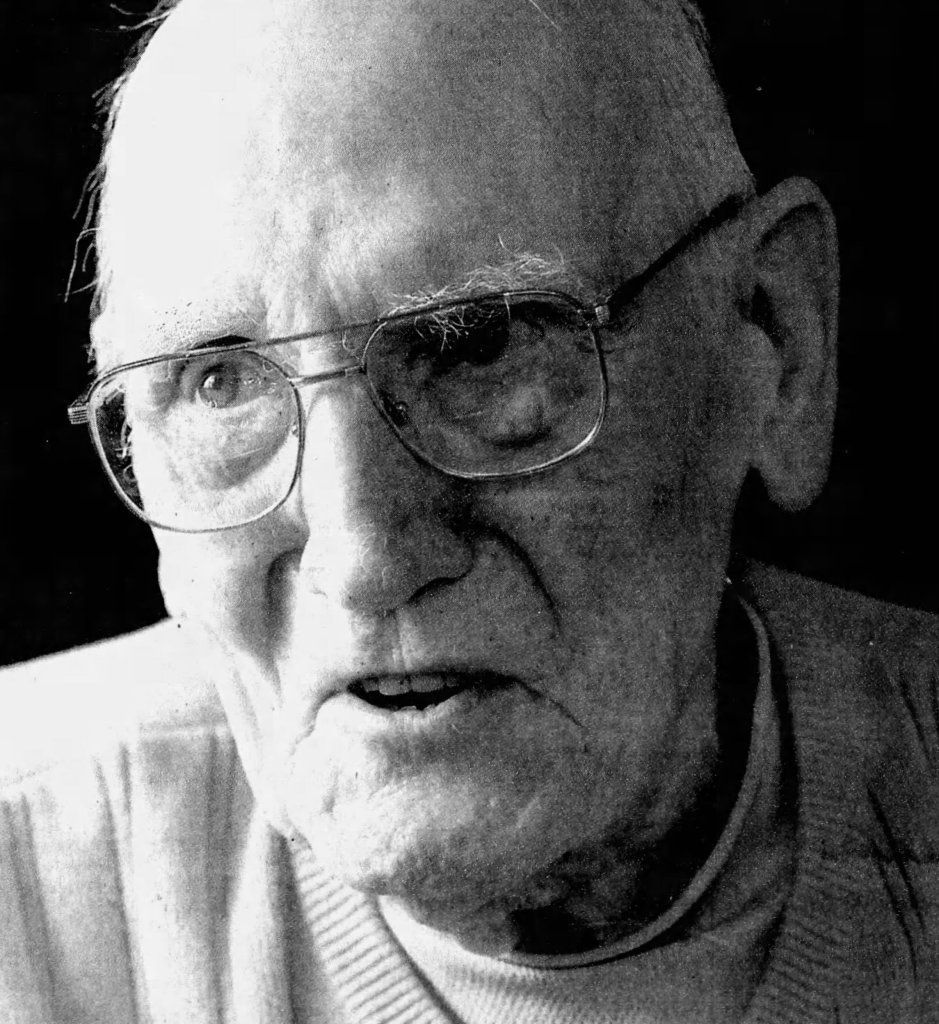

(Morning Call, 2001)

John Minnich was a truck driver with the Hawaiian Air Force at Wheeler Field. Explosions woke him. Dive bombers had hit the fighter base, and Zeros were screaming in. “About 50 of us from the transportation department started running across a field toward a little woods. We were like a pack of dogs, all scared and bunched together. I could see the Japanese pilots as their planes dived down and machine-gunned us. … The roar [of the Zeros] went right through me like an electric shock.”

From my interview with Minnich in the December 7, 2001, Morning Call

Paul Moyer was a private first class with the Army’s 21st Infantry Regiment at Schofield Barracks. After breakfast, he and two others left for a work detail that was to start at 8 a.m., but turned back when several Japanese planes flew overhead. “We stood there and watched them like idiots, until we saw the black smoke coming up from Wheeler Field. … We loaded up and got out of there, went to the Eucalyptus Forest to get ready for any kind of raid they might pull on us. A couple of days after the attack, we went to secure Kolekole Pass so the Japanese wouldn’t land troops at the big beach in back of it. … My dad received a telegram that I’d been killed in the Japanese attack. He didn’t know the truth for three months.”

From my interview with Moyer in the December 7, 2002, Morning Call

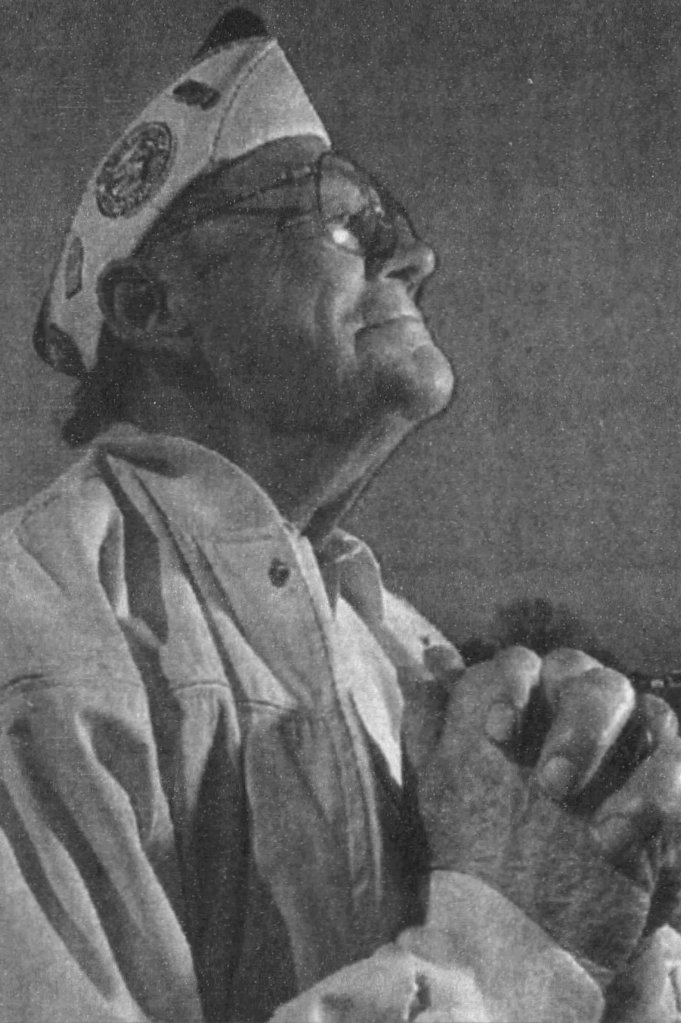

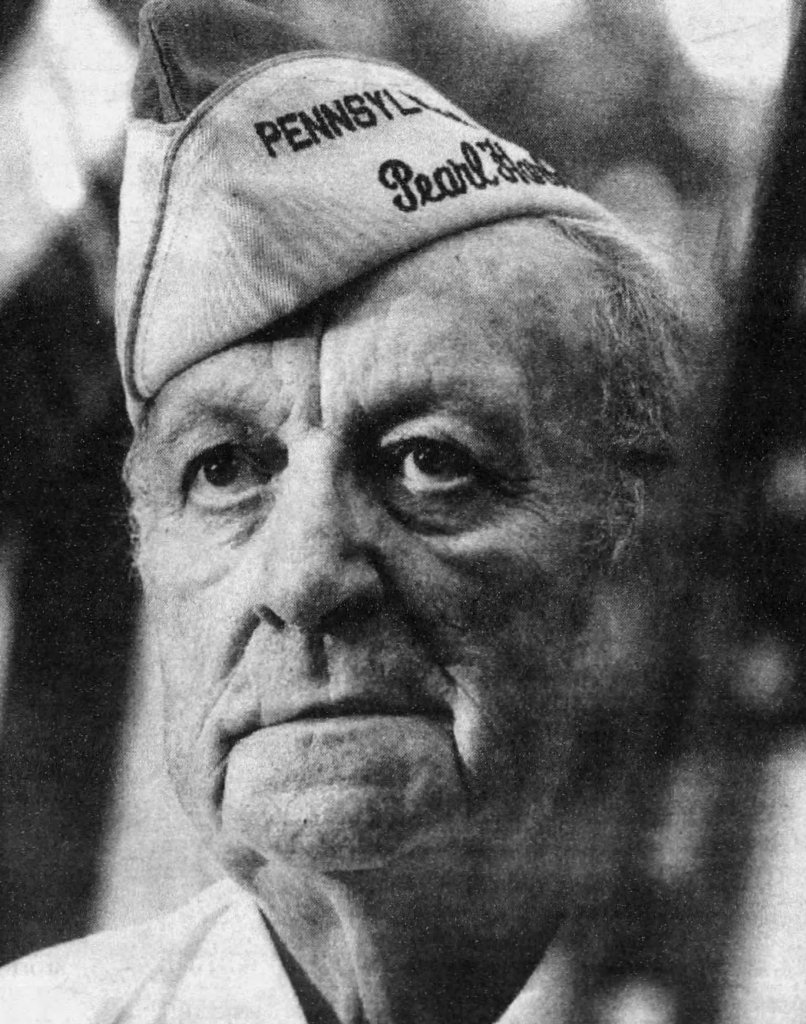

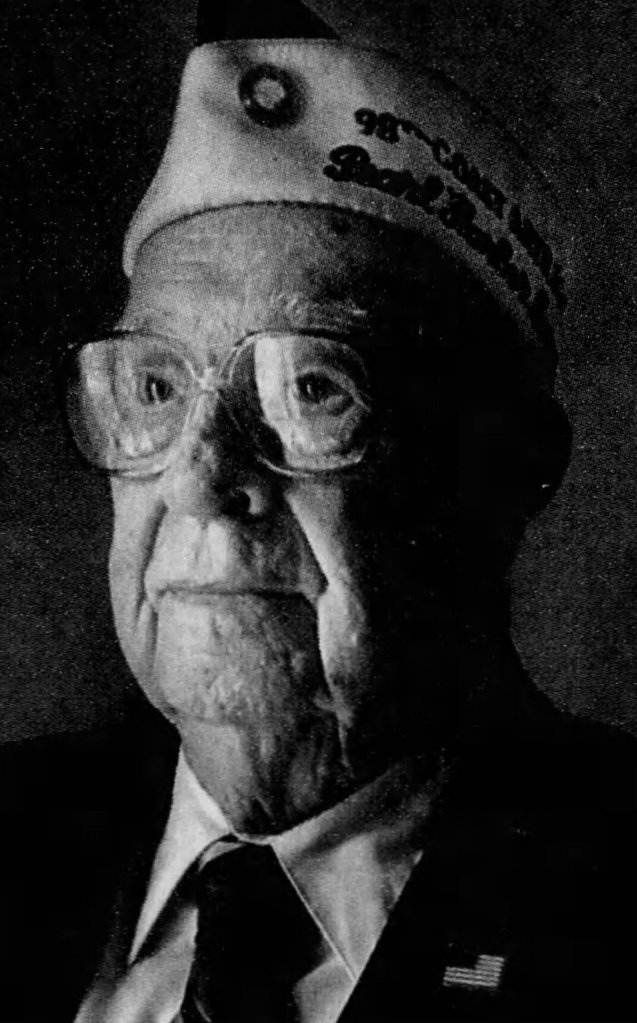

Joe Moore was a corporal and master gunner with the 98th Coast Artillery Regiment (Antiaircraft) at Upper Schofield, up a mountainside from the main Schofield barracks. “This one plane that had dropped his stuff at Wheeler came whoopin’ by with his machine guns running. He was low, just off the ground, strafing the area between our barracks and the one next door. You could see the dirt flying. … I was in the barracks when the island shook like it was having an earthquake. From the force of the jolting, I had a pretty good idea what had happened: A battleship was blowing up. Later that day, everybody knew what had happened to the USS Arizona.”

From my interview with Moore in the December 7, 2005, Morning Call

Clifford Ryerson was the navigator on the auxiliary minesweeper Tern, undergoing maintenance at the Navy’s 1010 dock across from Ford Island and Battleship Row. On December 7, Chief Quartermaster Ryerson and another sailor had the 4 to 8 a.m. watch. When the attack started, Ryerson saw planes flying “quite low” to torpedo the battleships. He fired at the enemy with the .45-caliber handgun he carried on his overnight watch. The Tern’s machine gunners opened up on an incoming plane. It crashed near the Officers Club – one of the 29 aircraft the Japanese lost that day.

From my interview with Ryerson and his son and daughter in the December 7, 2006, Morning Call

Warren Peters was a private first class in the Army’s 15th Coast Artillery at Fort Weaver, at the western entrance to Pearl Harbor. “There was an outfit right near us, and they had 3-inch antiaircraft guns. They were making all kinds of racket, and we were moaning the blues and all that: ‘Oh, it’s a Sunday morning, give us a break!’ That night, long after the attack, all of the men were at their guns. Several planes dropped flares to see where the landing fields were. “And when they did that, one big umbrella of fire went up from our antiaircraft guns — everybody firing at the planes from different angles. … Our gunners shot them all down. They were our own planes.”

From my interview with Peters in the December 7, 2008, Morning Call

Alfred Taglang was an Army supply sergeant in a Coast Artillery gun battery at Fort Kamehameha near the Hickam Field bomber base and Pearl Harbor. After shooting hoops that Sunday morning, he and a friend headed for 8 a.m. Mass. The attack began just as they got to the church. Low-flying enemy planes fired at the pair as they raced back to their quarters. “I saw dirt flying up from the bullets hitting the ground maybe 10 yards away.” He hurried to his 90-millimeter gun at Battery C. “My job was handing shells to the guy who loaded them into the gun. … We waited for our ammunition to come so we could join in the fight. Waited and waited and waited. … Our shells never arrived.”

From my interview with Taglang in the December 7, 2009, Morning Call

Burdell Hontz was an Army Air Corps corporal who worked in the message center of a B-17 bomber unit, the 11th Bombardment Group, at Hickam Field. He spoke of a friendly fire episode that happened after the Japanese attack got underway. “There was a group of fresh B-17s coming in from California. I could see them coming in for a landing, and these guys with rifles were shooting at them, and I yelled, ‘What the hell are you doing? Can’t you see they’re our planes?’ ” When Hontz had gotten up that morning, he decided to make his bed before going to breakfast, a task he didn’t ordinarily do. A bomb landed on the mess hall, killing 35 men. “I tell people I could have been a statistic, too, if I’d gone to breakfast. Thank God, I was making my bed.”

From my interview with Hontz in the December 7, 2010, Morning Call

(Morning Call, 2011)

Joe Lockard, Bob McKenney and Dick Schimmel all were in the Army Signal Corps Aircraft Warning Service on Oahu. Privates Lockard and McKenney worked at the Opana mobile radar station on the island’s northern tip. McKenney said he and Lockard “were the only experienced so-called crew chiefs there.” Schimmel, a private first class, was a plotter and switchboard operator at Fort Shafter, where an information center linked the island’s five radar sites.

Lockard lost a coin toss to McKenney and had to supervise the early shift at Opana. At 7:02 a.m., he and his partner, George Elliott, saw “a huge echo” on the oscilloscope, 136 miles out and closing fast. In a call that would put Lockard in the history books, he told Air Corps Lieutenant Kermit Tyler at the info center “we had never seen anything like this on radar, and that it obviously had to be planes.” Tyler said, “Don’t worry about it.”

Switchboard operator Joseph McDonald, feeling uneasy about what he had heard from the Opana site, went to the tent he shared with Schimmel, woke him and said, “Hey Shim, the Japs are coming.” Schimmel asked him to explain. “We were sitting there talking for a while,” Schimmel told me, “and all of a sudden BOOM! Here we thought the Navy was having a sham battle. Where we were situated, on a high plateau, we could look over and see Pearl Harbor. We ran out of the tent. We’d see a plane dive, hear an explosion and see smoke.” He and McDonald got up on the mess hall roof for a better view, then got their gear and ran to the info center to man the switchboard and plotting board.

Up north, the truck carrying Lockard and Elliott back to camp at Kawailoa passed one taking McKenney and others to Opana. “They were waving and shouting at us,” Lockard said, “but we couldn’t understand what they were saying. … When we got to Kawailoa, they told us we had been attacked. We knew immediately that what we had seen were those planes.”

From my story in the Sunday, December 4, 2011, Morning Call

Bob Kroner was a staff sergeant in the Army Signal Corps who led a team of cipherers in the Hickam Field control center. “We ran across the street to this building where three or four guys were working. … There were a lot of bombs dropping all around us. The guys were sending an SOS [by radio telegraph]. The message was in plain English: ‘SOS: Japs attacking Oahu.’ I sat down and started sending the SOS with the other guys. We kept sending it and sending it and sending it, hoping it would be picked up by the right people. All of a sudden, a bomb hit close to where I was. … Somebody yelled ‘Gas!’” Kroner hid in a back room, but there wasn’t any gas. He went back to sending the SOS.

From my interview with Kroner in the December 7, 2012, Morning Call

Gary Runey was an Army Air Corps future pilot stationed at Wheeler Field, where he taxied and maintained P-36 and P-40 fighters. He went to mechanic school at Hickam Field and was later moved to a tent area on the base’s perimeter. After guard duty until 6 a.m. December 7, he went to sleep and didn’t awake until the battleship Arizona blew up. “Three Zeros came to attack us. They were low down on the ground, maybe 20 feet up, going maybe 135 miles an hour and strafing. One went by, I could actually see the pilot clearly in his goggles.” No one was hurt, Runey said. Hours later, he saw a big truck on the access road to Hickam. “It was piled with bodies that they were taking out to a mortuary. It was pretty gruesome.”

From my interview with Runey in the December 7, 2015, Morning Call

—

May they rest in peace.

thank you so much for sharing the stories and remembering those men who I got to know very well over the years.

They were heroes but mostly great friends

LikeLike

Fantastic recap of our hero’s journey and story from th

LikeLike

Thanks, Rick.

LikeLike

Beautifully done, sweetheart! mv

LikeLike

Thank you so much for sharing. This is moving and and much nto remember.

LikeLike

Thanks, Fred.

LikeLike

Thanks for your salute to all these brave soldiers who defended our country!!

LikeLike